I. Canon and Claim

Why does Hamlet still sit at the centre of the literary canon? Why, for that matter, does Shakespeare still stand—seemingly immovably—at the head of world literature? What explains this stubborn, almost biological tenacity? Why Hamlet (1599-1601) and not another tragedy? Part of that answer lies in the play’s structure—which is less structure than centrifugal force—a revenge thriller that delays its revenge, a ghost story skeptical of its ghosts, a domestic drama that devours its own intimacies. Its contradictions are not flaws but motors. Hamlet doesn’t resolve: it revolves. Around death, grief, doubt, action, and the impossibility of certainty. Its meanings metastasize with each age, precisely because it refuses to be embalmed.

The customary arguments must be rehearsed, if only to be transcended: few writers have ever matched Shakespeare’s fusion of linguistic invention, emotional depth, and philosophical scope. His plays (Hamlet over and above all) are not simply texts to be read but instruments to be played: reinterpreted, recast, broken open by each epoch’s anxieties. No Shakespeare play can be neatly confined within any aesthetic, moral, or political code—and this is not incidental but essential. Resistance to containment is a watermark of canonical life. To be canonical is to be inexhaustible, to rupture frameworks rather than merely reflect them. Without this elasticity—this refusal to be fully domesticated by any era’s pieties—a work may be admired, even beloved, but it will not endure. Hamlet endures because it is more engine than edifice.

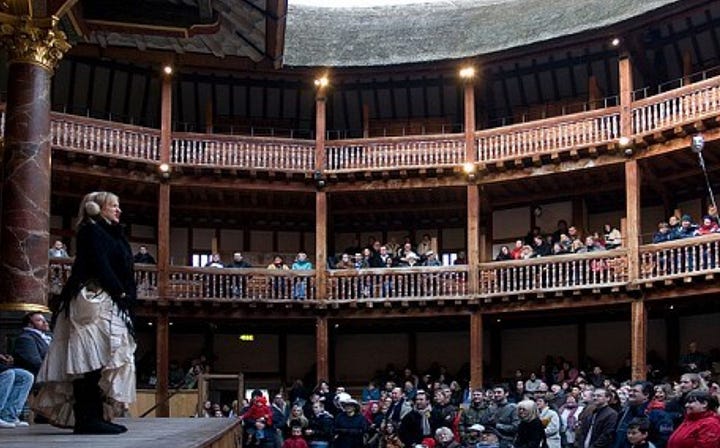

The canon—once a term of reverence, now a field of contest—is still shaped by what persists. Hamlet has likely been performed more than any other play in history. Tens of thousands of times. Translated into over seventy-five languages. Performed across more than ninety countries. Its reach—from the Globe Theatre, to Kenyan village squares, to prison camps, to astronauts aboard the International Space Station (ISS)—defies both (tangible) geography and (intangible) time. In the centuries since its debut, no play has traveled further, appeared in more forms, or invited more radical reinvention.

Adaptability is not an accident; it is the proof. Hamlet has been interpreted as the tragedy of pure thought (Romantics), repression (Freudians), textual instability (poststructuralists), and blank-slate local meaning (global directors). During the 2012 London Olympics, Shakespeare’s plays were reimagined by theatre companies from across the globe: Hamlet in Lithuanian, The Tempest through Bangladeshi myth, Titus Andronicus in Arabic. Even the more "obscure" plays found vibrant new mirrors—a Yoruba The Winter's Tale, a South Sudanese Cymbeline, a Maori Troilus and Cressida. Each culture found not accommodation but resonance. Elasticity is not mere openness; it is a kind of cosmic hospitality.

At the same London Olympics festival, England’s contribution was a production of Henry V—a choice that underscores this resistance in Shakespeare to singular appropriation. Henry V has long been celebrated as a patriotic anthem, famously invoking the "band of brothers" rallying at Agincourt.

HAL:

This day is called the feast of Crispian:

He that outlives this day, and comes safe home,

Will stand a tip-toe when the day is named,

And rouse him at the name of Crispian.

He that shall live this day, and see old age,

Will yearly on the vigil feast his neighbours,

And say ‘To-morrow is Saint Crispian:’

Then will he strip his sleeve and show his scars.

And say ‘These wounds I had on Crispin’s day.’

Old men forget: yet all shall be forgot,

But he’ll remember with advantages.

What feats he did that day: then shall our names.

Familiar in his mouth as household words

Harry the king, Bedford and Exeter, Warwick,

Tablot, Salisbury and Gloucester,

Be in their flowing cups freshly remember’d.

This story shall the good man teach his son;

And Crispin Crispian shall ne’er go by,

From this day to the ending of the world,

But we in it shall be remember’d;

We few, we happy few, we band of brothers;

For he to-day that sheds his blood with me

Shall be my brother; be he ne’er so vile,

This day shall gentle his condition:

And gentlemen in England now a-bed

Shall think themselves accursed they were not here,

And hold their manhoods cheap whiles any speaks

That fought with us upon Saint Crispin’s day.

Yet the play simultaneously complicates nationalism, staging Henry's ruthless manipulation of his troops, his casual cruelty toward traitors, and his uneasy justifications for conquest.

In Henry V’s Crispin’s Day speech, Shakespeare shows how memory, honour, and mortality become fused in the figure of the king. Beginning with a refusal to wish for more men, Henry transforms scarcity into a virtue, framing survival and sacrifice alike as routes to immortal renown. Earthly goods—gold, clothing, comfort—are dismissed in favour of an all-consuming desire for honour, a desire that paradoxically elevates the humble and the highborn alike. Through the promise of collective memory—"we few, we happy few, we band of brothers"—Henry imagines a future in which the trauma of battle is transfigured into a sacred narrative, passed from father to son. Glory, in Shakespeare’s vision, is less about personal triumph than about becoming part of an enduring story that binds the living and the dead across time.

This vision of memory as both burden and redemption casts a long shadow over Hamlet, where remembrance often feels like a curse rather than a blessing. In Hamlet, to be remembered is not simply to be honoured but to be trapped, ensnared by old debts, betrayals, and blood. Where Henry claims the authority to shape memory into unity and purpose, Hamlet is haunted by a memory he cannot command—his father’s death—thus revealing the darker underside of the same mechanism: the inescapable burden of the past.

England’s selection of Henry V reflected a national pride in Shakespeare’s literary genius, but it also revealed the tensions embedded in English identity itself: imperial ambition shadowed by doubt, heroism inseparable from violence. That Henry V could serve both as patriotic myth and anti-war critique demonstrates the same phenomenon evident across all of Shakespeare’s works: an inexhaustible elasticity. He does not belong to any one ideology, culture, or creed; he exceeds them all.

Shakespeare’s primacy in world literature is no longer automatic, but it is far from obsolete. In Hamlet, he does what almost no writer before or since has done: he holds the mirror up—not just to nature, as the play suggests—but to history, politics, psychology, and the theatrical form itself. We see the emotional bedrock of Hamlet’s despair articulated early, as he confronts the grotesque velocity of his mother’s remarriage:

HAMLET:

How weary, stale, flat, and unprofitable

Seem to me all the uses of this world!

Fie on ’t, ah fie! 'Tis an unweeded garden

That grows to seed. Things rank and gross in nature

Possess it merely.

As critic A.C. Bradley observes in Shakespearean Tragedy, Hamlet’s catastrophe pivots on his killing of Polonius—an act that triggers Ophelia’s madness and death—yet Hamlet remains, as Bradley notes, "the one we love the most." We love him because he is consciousness illuminated from within—not by virtue but by suffering. Harold Bloom expands: Hamlet is "the most intelligent character in all literature," a mind so expansive it watches itself watching itself. We love him because he names—with unparalleled wit, sadness, and irony—the most impossible truths: to know too much, to act too late, to suffer both knowledge and inaction with tragic grace.

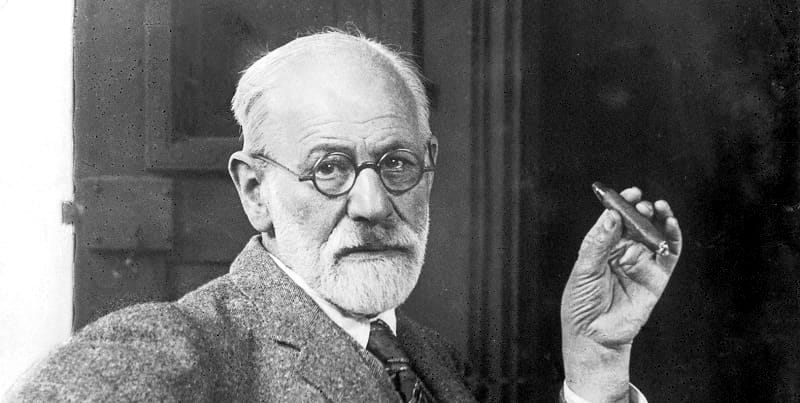

Bradley’s insight reminds us that Hamlet’s soliloquies and actions are driven by a deep, ceaseless inwardness—an interior war between duty and revulsion. Freud’s theory of the Oedipal complex radicalized this reading: Hamlet’s horror at Gertrude’s remarriage is not only grief but identification—the wish to replace the father, to possess the mother. The soliloquy is not only sorrow but subterranean guilt. The paralysis is not merely intellectual; it is psychic.

Theatre itself is mirrored, doubled, exposed: Hamlet stages a play within the play to "catch the conscience of the king." But in doing so, he ruptures theatrical convention: forcing audiences to become aware of their own watching, their own complicity. Reality and illusion collapse into each other. Hamlet’s consciousness infects the very structure of the drama. Shakespeare changes theatre—perhaps even human thought—forever. Theatre ceases to be the representation of action; it becomes the enactment of consciousness interrogating itself. A philosophical space, not just an aesthetic one.

Through Hamlet, Shakespeare anticipates modern existentialism, poststructuralism, and theories of performative identity—by centuries. He inaugurates a model of the tragic self as both actor and observer, caught in a hall of mirrors no decisive action can shatter. That he does so while entertaining audiences across four centuries—and across more than ninety countries—simply suggests a kind of imaginative force we are still learning how to recognize. Hamlet is not merely the story of a prince undone by grief; it is the birth of a new mode of consciousness on the stage—a consciousness that, once awakened, could never again be put to sleep.

II. The Structure of Contradiction

One of the most remarkable qualities about Hamlet is its resistance to formal categorization. It is a revenge tragedy that delays its revenge, a philosophical drama that never settles on a doctrine, a ghost story that questions the reality of its own spectres . . .

From the very beginning, when the ghost appears and "the morn in russet mantle clad, walks o’er the dew of yon high eastern hill" (Act 1, Scene 1), the play signals a world where the natural and the supernatural bleed into one another. One imagines Denmark as rendered in the chilling, mist-drenched canvases of painters like Eugène Delacroix and John Everett Millais—where shadow smothers light. The air itself seems to carry the weight of secrets. The colours of Hamlet are these: muted iron-grey, ash-white, blood-rust red, and the deep, bruised blues of approaching night.

In stagings of Shakespeare's Denmark, colour itself becomes a symptom of rot, a visual proof of a kingdom where nature and the unnatural have collapsed into one another, where every shade seems tinged with an undertow of death. The colour palettes are often dominated by cold steel blues, sterile whites, and deep black shadows—a visual language of paranoia and moral collapse. The visual atmosphere, like Hamlet’s mind, is surely a labyrinth of reflections, surveillance, and unsteady surfaces even in"closet drama" readings.

The play’s structure is famously asymmetrical: long stretches of psychological inquiry punctuated by abrupt bursts of action. This tension—between narrative drive and meditative delay—creates a kind of existential drag. Events occur not because of plot necessity, but because of pressure building within characters who no longer fully trust their own roles. When Hamlet contemplates the ghost’s commands, he hesitates: "The spirit that I have seen / May be a devil" (Act 2, Scene 2), wary that the very framework of his revenge might be false.

Hamlet refuses the Aristotelian unities of time, place, and action. It meanders, loops, doubles back endlessly. The climax is not clearly marked; the resolution feels provisional. There are scenes—like the travelling players’ performance, the graveyard exchange with the gravedigger, or Hamlet’s musings over Polonius’s corpse—that would feel like digressions in any other tragedy. And yet these scenes are where the pulse of the play lives.

Even the ghost—which initiates the revenge plot—has the uncanny effect of pausing the narrative rather than propelling it. Hamlet’s encounter with the ghost does not trigger immediate action but a descent into introspection:

HAMLET:

What may this mean,

That thou, dead corpse, again in complete steel,

Revisits thus the glimpses of the moon,

Making night hideous?

(Hamlet Act 1, Scene 4).

It is as if the ghost opens not a door to resolution but a hall of mirrors. Every character that enters this space becomes a version of Hamlet—Laertes, Fortinbras, Ophelia—all fractured by grief, duty, or doubt.

This structure mirrors Hamlet’s own dilemma. He is a character caught between narrative conventions: the call to avenge his father, and the deeper call to understand why vengeance feels hollow. As a result, the play does not so much progress as deepen. It circles its themes—death, memory, performance, loyalty, delay—like a piece of music with variations rather than a linear argument. In Hamlet’s words, "The time is out of joint: O, cursed spite, / That ever I was born to set it right!" (Act 1, Scene 5).

The result is not a failure of form, but a radical reimagining of it. In traditional models of tragedy—inherited from Aristotle and the medieval "Great Chain of Being"—action restores cosmic balance: wrong is answered by right, disorder by order. Revenge, in such systems, is not only permitted but sanctified, part of the natural restoration of justice. Hamlet destabilizes this certitude.

The hero does not accept the inherited moral structure without question; he suspects it, interrogates it, and ultimately suffers for that interrogation. His hesitation is not mere indecision, but a metaphysical vertigo: what if action itself deepens the world's corruption rather than cures it? Shakespeare shifts the tragedy from the external workings of fate to the internal collapse of epistemology. As Northrop Frye observes in his Anatomy of Criticism:

Hamlet marks the emergence of a tragic hero who is aware of the conventions that bind him, yet powerless to escape them. The play makes the tragic process itself a subject of its own inquiry.

Shakespearean tragedy thus turns its lens inward: not simply to depict a fall, but to interrogate the very machinery by which a fall is staged. Knowledge, perception, and moral judgment themselves become suspect. In this way, Hamlet does not merely revise the tradition—it ruptures it, inaugurating a new tragic consciousness that modernity has never escaped. T.S. Eliot famously declared that "Hamlet is the Mona Lisa of literature, a work that compels fascination more than it yields explanation." This opacity is not a flaw to be solved but a defining feature: the impossibility of fully knowing or fully judging becomes the tragedy’s hidden centre. Hamlet asks what a tragedy can be if its hero knows too much to simply play the part he's been given. Like its protagonist, the play remains unfinished by design.

III. Hamlet the Character: Intelligence, Delay, and the Self as Performance

Hamlet’s singularity lies not only in what he says, but in how he seems to know what he is saying. Hamlet’s singularity is revolutionary: for the first time in Western drama, a character becomes radically self-conscious not merely about his own motives but about the very nature of performance, perception, and action. He is hyper-conscious—aware of the theatre he’s in, of the politics around him, of the limitations of language itself. Hamlet is not merely a prince set against the world; he is a mind that interrogates the very possibility of meaning within that world. When he says, "Seems, madam? Nay, it is. I know not 'seems'" (Act 1, Scene 2), he draws an immediate, chilling line between appearances and reality, between performed emotion and genuine feeling. It is a declaration not only of grief but of ontological crisis—a refusal to accept the inherited scripts of identity, mourning, and duty. His is a mind constantly folding in on itself, knowing not only that he must act, but that all action is tainted by performance, by the untrustworthiness of gesture and speech. As Lionel Trilling would later describe the modern self in literature, Hamlet is among "those whose consciousness is at war with the conditions of their existence," a consciousness that could no longer trust the seamlessness of being but had become estranged, splintered, infinitely reflexive.

His delay—so long debated by critics—is not simply weakness, nor simple indecision. It is an ethical hesitation of a radically new kind. Hamlet's struggle is not with fear alone but with meaning itself: he hesitates because the call to revenge may be a false summons, a temptation by evil forces masquerading as duty. He does not trust the ghost without testing it, and even when opportunity presents itself—when Claudius prays alone—he withholds his hand, reasoning, "Now might I do it pat, now he is praying; / And now I'll do't—and so he goes to heaven" (Act 3, Scene 3). His refusal to act according to genre expectation is nothing less than a revolt against the entire moral architecture that previous tragedies assumed.

This introduces a new tragic mechanism: self-scrutiny replaces instinct, suspicion supplants righteous action, and Hamlet’s own mind becomes a second stage upon which every motive must audition, every instinct be doubted, every narrative be picked apart before it can lead to action. His tragedy is not simply that he delays, but that he delays for good reason—and that in doing so, he renders traditional forms of tragic inevitability obsolete. Hamlet resists the genre he’s been written into. He knows how revenge tragedies work, knows the expected role he is meant to embody, and he refuses to proceed blindly. He must remake the script—even if that means leaving it unfinished, even if that means leaving himself broken inside the ruins of the play he refuses to perform.

This resistance touches the heart of the play’s meta-theatricality. In As You Like It, Shakespeare had mused:

JACQUES:

All the world's a stage,

And all the men and women merely players;

They have their exits and their entrances,

And one man in his time plays many parts,

His acts being seven ages. At first the infant,

Mewling and puking in the nurse’s arms;

And then the whining school-boy, with his satchel

And shining morning face, creeping like snail

Unwillingly to school. And then the lover,

Sighing like furnace, with a woeful ballad

Made to his mistress’ eyebrow. Then a soldier,

Full of strange oaths, and bearded like the pard,

Jealous in honour, sudden and quick in quarrel,

Seeking the bubble reputation

Even in the cannon’s mouth. And then the justice,

In fair round belly with good capon lin’d,

With eyes severe and beard of formal cut,

Full of wise saws and modern instances;

And so he plays his part. The sixth age shifts

Into the lean and slipper’d pantaloon,

With spectacles on nose and pouch on side;

His youthful hose, well sav’d, a world too wide

For his shrunk shank; and his big manly voice,

Turning again toward childish treble, pipes

And whistles in his sound. Last scene of all,

That ends this strange eventful history,

Is second childishness and mere oblivion;

Sans teeth, sans eyes, sans taste, sans everything.

(As You Like It, Act 2, Scene 7)

Yet in Hamlet, Shakespeare transforms this insight: what was philosophical musing in As You Like It curdles into a corrosive, existential vision. The recognition that life is composed of roles—each as transient, hollow, and predetermined as the last—leads not to acceptance but to profound existential nausea. Hamlet understands that if all identity is merely performance, then authenticity itself becomes suspect. His tragedy is that he is too conscious of his parts, too aware of the script, and thus paralyzed before each entrance and exit. Where Jaques in As You Like It reflects passively on life’s inevitable stages, Hamlet confronts the terror that those stages might be meaningless—that the entrances and exits lead nowhere, that the script is not divinely ordained but arbitrarily imposed. In this, Hamlet is Shakespeare’s greatest act of philosophical insurgency: he transforms the theatre from a mirror of life into an abyss reflecting our deepest uncertainties about whether life has any coherent form at all. Jaques's speech in As You Like It accepts life's mutability as an inevitable procession—a series of roles played until they fade into "second childishness and mere oblivion." Hamlet, by contrast, cannot endure such passive acceptance. His outcry in Act 1—"How weary, stale, flat, and unprofitable / Seem to me all the uses of this world!"—shows a soul for whom the very stages of existence have become intolerable. Where Jaques surveys life's drama from a wry, ironic distance, Hamlet feels trapped within a play he has not authored, forced into parts whose falseness he perceives too acutely to perform without agony.

Thus, while Jaques sketches life’s seven ages with cool detachment, Hamlet embodies the terror that there may be no script worth following, no narrative arc that redeems the passage from cradle to grave. The existential nausea Hamlet expresses is not simply personal grief—it is the sickness of consciousness itself when it sees that every role, every act, every meaning may be arbitrary, hollow, imposed. If all the world is performance, where can authenticity be found? Hamlet understands that if identity itself is theatrical, if every role is an inherited script, then truth becomes elusive—perhaps impossible.

This radical self-consciousness infiltrates every aspect of Hamlet's being, but nowhere is it more devastatingly visible than in his speech. His meta-awareness extends into his language, transforming even his most intimate expressions into acts of performance, self-scrutiny, and disintegration. No character in Shakespeare modulates tone with more speed—he shifts from comedy to contempt, from grief to irony, often within a single line. His language is a performance of selfhood, but one that is constantly falling apart. In his most famous soliloquy—"To be, or not to be, that is the question" (Act 3, Scene 1)—he speaks not as an actor, prince, or son, but as a mind trying to catch up with its own dread. The soliloquy doesn’t resolve anything. It reveals that thought, like the play itself, is recursive, bound by its own form.

I have transcribed the speech in its entirety:

HAMLET:

To be, or not to be, that is the question:

Whether 'tis nobler in the mind to suffer

The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune,

Or to take arms against a sea of troubles

And by opposing end them. To die—to sleep,

No more; and by a sleep to say we end

The heart-ache and the thousand natural shocks

That flesh is heir to: 'tis a consummation

Devoutly to be wish'd. To die, to sleep;

To sleep, perchance to dream—ay, there's the rub:

For in that sleep of death what dreams may come,

When we have shuffled off this mortal coil,

Must give us pause—there's the respect

That makes calamity of so long life.

For who would bear the whips and scorns of time,

Th'oppressor's wrong, the proud man's contumely,

The pangs of dispriz'd love, the law's delay,

The insolence of office, and the spurns

That patient merit of th'unworthy takes,

When he himself might his quietus make

With a bare bodkin? Who would fardels bear,

To grunt and sweat under a weary life,

But that the dread of something after death,

The undiscovere'd country, from whose bourn

No traveller returns, puzzles the will,

And makes us rather bear those ills we have

Than fly to others that we know not of?

Thus conscience doth make cowards of us all,

And thus the native hue of resolution

Is sicklied o'er with the pale cast of thought,

And enterprises of great pith and moment

With this regard their currents turn awry

And lose the name of action.

(Hamlet Act 3, Scene 1)

The textures of Hamlet’s speech underscore his crisis. One moment he mourns "the uses of this world" as "weary, stale, flat, and unprofitable" (Act 1, Scene 2), another he accuses Ophelia of duplicity with a sneering cruelty. Oscillating between sublime philosophical lament and savage wit, his language mirrors the collapse of any stable self. His speech patterns reveal not mastery, but fracture.

Even Hamlet’s wit is double-edged. His jokes sting not just others but himself. When he remarks to Polonius, "Though this be madness, yet there is method in't" (Act 2, Scene 2), he toys with perception, protecting himself behind irony. Yet this armor is porous. As Kierkegaard noted in The Concept of Irony, irony shields the individual from despair by refusing to accept the given meanings of the world—but it simultaneously exacerbates existential isolation by stripping away all stable ground for belief or action.

For Kierkegaard, irony is "a boundary that delimits the finite from the infinite," and Hamlet lives within that boundary: too conscious to surrender to convention, too skeptical to act without inner sabotage. Hamlet’s irony distances him from pain—but the cost is alienation, an inward severing that no action can truly mend.

I have of late—but wherefore I know not—lost all my mirth, forgone all custom of exercises; and indeed, it goes so heavily with my disposition that this goodly frame, the earth, seems to me a sterile promontory

(Act 2, Scene 2), Hamlet confesses to Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, embodying his collapse into despair. Even as he perceives the beauty of the world and "what a piece of work is man," he feels its utter nullity. His despair is not that the world has lost its order, but that he can no longer believe in any order without irony.

Hamlet is not a hero. He is a figure of modernity: fractured, skeptical, brilliant, and deeply alone. He speaks with prophetic clarity and still cannot act. He sees through illusion and still walks into traps. He suspects the script, and yet, he cannot escape it. He is not an answer. He is a paradox in motion—and it is this tension that keeps him alive on the stage, in print, and in the imagination of every age that inherits him. Hamlet is not simply a character; he is a mode of being—the consciousness that recognizes all action as theatrical, all identity as provisional, and yet must go on living, brilliantly and brokenly, under the weight of that knowledge.

IV. The Play as a Philosophical Text

Hamlet is not merely a literary work but a philosophical labyrinth. It is Shakespeare’s most relentless interrogation of reality, meaning, and selfhood—concerns that would echo in the works of Descartes—whose meditations on doubt and selfhood mirror Hamlet’s inner crisis—and whose cogito ergo sum could be seen as the philosophical crystallization of the very condition Hamlet dramatizes. Hamlet's radical doubt—his refusal to accept the given narratives of action and meaning without interrogation—anticipates Descartes' own method of universal doubt. It is Hamlet who, centuries before Descartes, embodies the realization that the foundation of knowledge must be sought within the self’s capacity for skepticism. Our modern understanding of the self—as something fractured, reflexive, and capable of interrogating its own being—is thus prefigured in Hamlet and philosophically formalized in Descartes' Meditations.

Hamlet thinks, therefore he suffers; Descartes thinks, therefore he is. But the ground had already been broken by Shakespeare, whose prince of Denmark dramatized a consciousness in conflict with itself before the philosophical language for such conflict even existed—in Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, Camus, Dostoevsky, Proust, and Beckett. Dostoevsky's Raskolnikov is a direct descendant of Hamlet, a consciousness consumed by guilt and doubt; Proust's involuted self in In Search of Lost Time owes its structure to Hamlet’s recursive soliloquies; and Beckett’s figures—estranged, suspended between thought and action—reimagine Hamlet’s paralysis on the barren stage of the absurd. The play’s obsession with thought—its power, its limits, its paralyzing consequences—makes it arguably the most philosophical of Shakespeare’s works. It is not philosophy in the systematic sense, but philosophy rendered theatrical: embodied, spoken, agonized over.

When Hamlet asks, "To be, or not to be, that is the question" (Act 3, Scene 1), he does not seek an answer but rather dramatizes a mode of inquiry that resists resolution. The question is existential, not just in content but in form—it leaves the audience suspended between action and abstraction, suspended like Hamlet himself. His mind does not simply reflect the world; it refracts it, bending experience through skepticism and speculation. This dramatization of radical uncertainty anticipates the philosophical breakthrough of Descartes, whose Meditations begin with methodical doubt and proceed only by recognizing that the very act of doubting confirms the existence of a thinking self. Hamlet’s soliloquy enacts a similarly vertiginous self-recognition: he is aware that thought itself constructs, deconstructs, and ultimately paralyzes will. "Thus conscience does make cowards of us all," he concludes (Act 3, Scene 1), grasping what Descartes would later codify—that consciousness, severed from any external guarantees of truth, becomes both the source of selfhood and its prison.

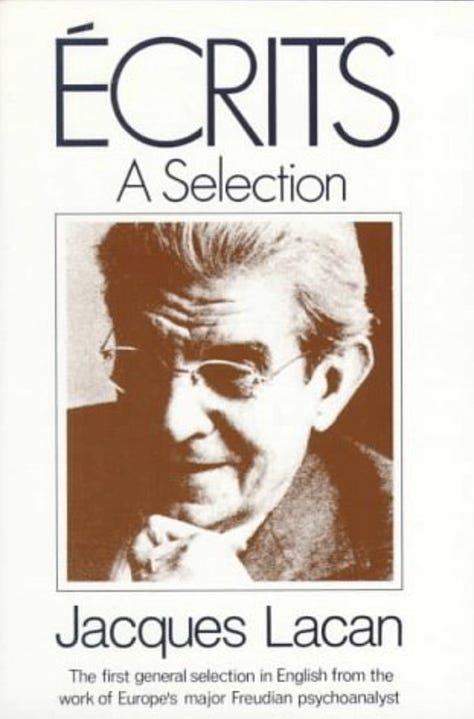

Much of the play’s philosophical force arises from its treatment of language—a treatment that anticipates the deconstructive theories of Jacques Derrida. Derrida’s famously cited "there is nothing outside the text," suggests that meaning is never fixed, but endlessly deferred within systems of signs. Hamlet instinctively senses this: words in his world no longer anchor truth but circulate ambiguously, breeding uncertainty rather than resolving it. Words in Hamlet are slippery, unstable, and sometimes hollow. "Words, words, words," Hamlet mutters to Polonius (Act 2, Scene 2), expressing the fatigue of a world where language has lost its grounding. Later, when Hamlet is pressed by Guildenstern to explain himself, he responds, "You would pluck out the heart of my mystery" (Act 3, Scene 2). But the heart resists.

Language, like memory, fails him. Hamlet tries on voices—ironic, sincere, savage, speculative—but none quite suffice. "O, what a rogue and peasant slave am I!" (Act 2, Scene 2) he exclaims—not as a confession, but as a rehearsal. His soliloquies are not declarations but experiments in thinking. The play becomes a portrait of what Wittgenstein would later call the limits of language—what cannot be said must be shown, or lived, or endured. Silence, too, speaks. In this world where signs collapse under their own weight, Jean Baudrillard's later observation that "we live in a world where there is more and more information, and less and less meaning" finds an uncanny prefiguration. In Hamlet, as in Baudrillard's postmodern landscapes, acts of communication multiply without securing understanding; language becomes a hall of mirrors in which the self struggles to retain coherence.

As previously stated, there is no doctrine in Hamlet, only tensions: tensions between knowing and acting, being and seeming, speaking and silencing. If King Lear explores the breakdown of the world, Hamlet explores the breakdown of self. What does it mean to think too much, to speak too precisely, to doubt so deeply that even one’s motives blur? These are not merely philosophical questions; they are theatrical ones. And that is Shakespeare’s innovation: to make metaphysics into drama. Hamlet is philosophy with a pulse.

V. Hamlet Compared to Shakespeare’s Other Tragic Heroes

Hamlet represents not merely the deepening of character but the rupture and reinvention of the tragic form itself: for the first time, tragedy moves from the external catastrophes of fate to the internal collapse of consciousness. In Hamlet, Shakespeare does not refine the tragic hero—he detonates him, creating the fractured modern subject who will haunt the literature and cinema of every century to follow.

If Hamlet changed the stage, he also changed the very concept of the tragic hero. As Harold Bloom observes in Shakespeare: The Invention of the Human, "Hamlet is not only Shakespeare’s greatest play but also the play that most fully embodies his discovery of what it is to be human." Shakespeare’s earlier figures—Richard III, Romeo, Brutus—all hinted at psychological complexity, but Hamlet marks a seismic shift: from passion to thought, from action to self-interrogation.

Shakespeare had already experimented with inner conflict. Richard III is witty and self-aware, but his villainy is almost gleeful, not tortured. His evil is straightforwardly motivated, rooted in resentment and deformity. Early in the play, Richard himself cites his own physical deformity as the source of his malice:

RICHARD III:

I, that am curtailed of this fair proportion,

Cheated of feature by dissembling Nature,

Deformed, unfinished, sent before my time

Into this breathing world scarce half made up

(Richard III, Act 1, Scene 1).

His path to villainy is almost a logical reaction against a world that mocks and rejects him.

The resolution of Richard’s arc—the visitations of the ghosts of his victims the night before the Battle of Bosworth Field—is dramatically effective but psychologically simplistic. The ghosts (including Prince Edward, Henry VI, Clarence, Rivers, Grey, Vaughan, the two young princes, Hastings, Lady Anne, and Buckingham) curse Richard and bless his adversary Richmond. One of the most famous lines from this scene comes from the ghost of Prince Edward: "Think on Lord Hastings. Despair, and die!" These repetitive visitations offer a moral reckoning rather than a deepened understanding of Richard’s own inner collapse. The tragedy here remains within the medieval moral structure: sin is punished, evil is vanquished. Richard’s self-awareness does not lead to existential paralysis; it leads to external defeat.

Romeo dies for love, but he is ruled by impulsive feeling, not philosophical despair. Brutus, torn between loyalty and principle, shows a noble idealism, but his doubt remains political, not metaphysical. In Hamlet, for the first time, Shakespeare stages a mind turned brutally against itself, where the tragedy is not of circumstance alone, but of consciousness.

Compared to Hamlet, Shakespeare’s later tragic heroes seem almost elemental. Macbeth, driven by ambition and external prophecy, hesitates only briefly before plunging into bloody action. Othello, manipulated by Iago, is undone by jealousy—his tragedy lies in misplaced trust, not in metaphysical dread.

Unlike Hamlet, whose paralysis stems from metaphysical dread and the collapse of the symbolic order, Othello’s destruction emerges from an intensely human vulnerability: the need for trust, the terror of betrayal, and the fragility of identity in a world saturated by appearances and insinuations. Othello's fall is devastating not because he is simple, but because he is catastrophically human—capable of overwhelming love and overwhelming doubt. Othello’s complexity lies not merely in the extremity of his jealousy but in the profound emotional cosmology that defines his sense of self. His love for Desdemona is not merely personal but existential; it constitutes the fragile architecture of his very being. This becomes painfully evident in a pivotal moment of Othello when he says:

OTHELLO:

Perdition catch my soul,

But I do love thee! and when I love thee not,

Chaos is come again.

(Othello, Act 3, Scene 3)

In these lines, Othello stakes the entire order of existence on the stability of his passion. The specter of "chaos" here is not rhetorical: it signals a collapse of both private and cosmic coherence, where love is the last bastion against an engulfing void. Unlike Hamlet’s philosophical musings, Othello's catastrophe is rooted in the catastrophic fragility of human trust. If Hamlet’s tragedy emerges from the paralysis of thought, Othello’s tragedy arises from the unbearable volatility of feeling. This distinction makes Othello’s fall not less profound, but differently catastrophic: an emotional apocalypse rather than a metaphysical one. His collapse is emotional rather than metaphysical, but it is no less total; Othello, like Hamlet, is ultimately betrayed by his own faith in the meaning of words, the promises of others, and the stability of his own perception.

Lear discovers human fragility through suffering, but his collapse is emotional, not philosophical. Even Coriolanus, a titan of pride and martial virtue, falls through political rigidity, not through paralyzing thought. As Marjorie Garber outlines in her breakdown, his creative arc1 can be divided into four stages: the exuberant early histories and comedies; the major tragedies of the middle period; the dark, experimental "problem plays"; and finally, the late romances. Coriolanus, one of Shakespeare's final tragedies, belongs to this late, post-Hamlet phase. Yet even at this mature stage, Shakespeare does not replicate the radical interiority of Hamlet. Coriolanus is rigid, magnificent, and doomed by his inflexibility, but he does not descend into philosophical disintegration. His tragedy lies in a failure to adapt to political realities, not in a collapse of the self. Coriolanus cannot betray his nature—but he does not doubt it. Hamlet, by contrast, lives in a hall of mirrors where every certainty is corroded from within.

Hamlet’s tragedy is singular because it occurs within. He knows too much to act simply; he doubts too deeply to escape action. Where Macbeth rushes toward fate and Lear blunders into ruin, Hamlet lingers, circles, and contemplates. His language, dense with puns, ironies, and contradictions, enacts his predicament: to live is to think, but to think is to fall apart.

This evolution is not merely a refinement of earlier models but a rupture. Classical tragedy, from Aeschylus to Sophocles, pitted man against inexorable fate. Shakespeare’s earlier tragedies pit man against passion. Hamlet inaugurates a third model: man against his own consciousness. The hero does not suffer because he is blind, but because he sees too much.

Hamlet’s internal torment has clear antecedents, yet he transcends them. Seneca’s tragedies, which greatly influenced the Elizabethan stage, dramatize stoic endurance in the face of horror. Thyestes, for example, suffers cosmic injustice, but the internal life is relatively static—"Amid such ills it is a lesser thing to suffer death." The focus remains on suffering itself, not on the psychic fragmentation it provokes.

Similarly, Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus portrays a man who agonizes over his damnation, but even Faustus’ struggle is largely linear: ambition, bargain, despair. Faustus cries, "Why, this is hell, nor am I out of it," yet his damnation is theological, not existential. Hamlet’s despair, by contrast, fractures his identity itself; his doubt does not merely condemn him, it unravels him.

Compared to these antecedents, Hamlet represents a staggering leap in psychological realism. The tragedy unfolds not merely through external catastrophe, but through a collapse inward, through thought's metastasis into paralysis.

Thus, Hamlet becomes the prototype of modern alienation. Without Hamlet, there is no Raskolnikov, no Meursault, no Vladimir and Estragon. In Hamlet, Shakespeare invents the self-tormenting mind that defines the literature of modernity—a consciousness so vast, so broken, so luminous in its ruin, that it continues to haunt every art that follows.

VI. Hamlet and the Tragic Philosophers: Schopenhauer, Hegel, Nietzsche

Hamlet is not only Shakespeare's most philosophical hero; he is also the earliest embodiment of the tragic insights that would preoccupy Schopenhauer, Hegel, and Nietzsche. Each of these thinkers—predating the twentieth-century Existentialists—in their own way, grappled with the implications of a world where certainty erodes, will collapses into reflection, and knowledge cripples rather than empowers. Hamlet is not merely a character; he is the first full dramatization of the tragic modern self. His crisis is no longer merely external—it is a crisis of being, perception, and knowledge itself.

To trace the deeper currents of Hamlet’s despair—the Schopenhauerian nausea toward existence, the Hegelian paralysis of moral contradiction, and the Nietzschean exhaustion before the void—we turn not to the familiar "To be, or not to be," but to an earlier soliloquy that lays bare the unbearable weight of being from the very outset:

HAMLET:

O, that this too too solid flesh would melt,

Thaw and resolve itself into a dew!

Or that the Everlasting had not fix'd

His canon 'gainst self-slaughter!

(Hamlet, Act 1, Scene 2)

In these opening lines of the soliloquy, Hamlet wishes for annihilation but feels trapped by divine prohibition against suicide. He is imprisoned not just by circumstance but by existence itself—caught in the contradiction between the desire for oblivion and the structures that forbid it.

Arthur Schopenhauer, in The World as Will and Representation, memorably writes: "Life is a constant dying. The will-to-live, which holds us in the world, is a ceaseless striving without final satisfaction." For Schopenhauer, existence itself is suffering, produced by endless, blind striving. To recognize the futility of this striving is, for Schopenhauer, the beginning of wisdom—and the beginning of tragic awareness. Hamlet’s wish that his "solid flesh" would melt captures precisely this Schopenhauerian nausea toward the burden of existence. Hamlet does not simply mourn; he rejects the very machinery of being. He sees life itself as an "unweeded garden" overrun by "things rank and gross in nature"—a landscape of decay, echoing Schopenhauer's vision of the world as a monstrous, ceaseless striving without redemption.

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel—also following the influence of Hamlet—in The Phenomenology of Spirit, articulates tragedy as: "The tragic collision is not between right and wrong but between right and right." Classical tragedy—such as Sophocles' Antigone—pits two ethical worlds against one another. But modern tragedy, he suggests, internalizes this contradiction within the individual. Hamlet enacts precisely this shift. His duty to avenge his father clashes against his emerging ethical resistance to vengeance itself. The clash is not between Hamlet and the world; it is within Hamlet’s very soul. His paralysis is not a mark of weakness, but the symptom of a Hegelian tragic consciousness, where the reconciliation of moral imperatives becomes impossible. Hamlet, caught between competing ethical spheres—feudal honor, Christian forgiveness, and philosophical skepticism—suffers from the “modern condition”: a collapse of action into thought.

Likewise, Friedrich Nietzsche, in The Birth of Tragedy, describes the tragic condition as “an aesthetic phenomenon that existence and the world are eternally justified." Nietzsche distinguishes between the Apollonian impulse (order, rationality, form) and the Dionysian impulse (chaos, suffering, ecstasy). Tragedy arises when the Apollonian frame is shattered by Dionysian terror—the vision of existence as fundamentally meaningless. Hamlet, Nietzsche writes, is the Dionysian man par excellence: "He has seen into the essence of things, and he finds action repugnant; for his action can change nothing in the eternal nature of things."

When Hamlet wishes for his flesh to "melt," it is the Dionysian exhaustion that speaks—a rejection of the entire burden of appearances, conventions, and inherited obligations. He has glimpsed the void behind the world's fabrications and cannot unsee it. Action becomes absurd; existence itself becomes suspect.

Together, Schopenhauer, Hegel, and Nietzsche show us that Hamlet is not merely the first modern hero. He is the first modern problem: the awareness that to act in the world, to live, to will, is itself entangled with futility, contradiction, and self-destruction. The birth of philosophy from tragedy—the tragic interrogation of will, action, and knowledge—begins with Hamlet.

Through Hamlet, Shakespeare did not just give the world a mirror; he gave it its first philosophical labyrinth, one we have never truly escaped. In the corridors of Hamlet's mind, we encounter ourselves: suspended between knowing and acting, desiring and despairing, living and questioning the very worth of life.

VI. The Transformation of the Self: From the Ancient to the Modern

The ancient conception of the self was comparatively stable. In Greek and Roman tragedy, individuals were defined by their roles within the cosmic, political, and familial orders. The self was exteriorized (not interiorized): character was fate made visible, virtue or hubris acted out upon the stage of the world. Oedipus, Antigone, and (even Shakespeare’s own) Brutus are figures whose interior lives are largely opaque; they are shaped by duty, destiny, and external law. Their suffering is real, but it is driven by conflicts between external imperatives rather than by agonizing introspection. As Aristotle frames it in the Poetics, tragedy was concerned with action, not with the complexities of psychological self-interrogation. Homer's Achilles and Odysseus, Sophocles' Oedipus, Virgil's Aeneas—all reveal selves defined by their alignment to or rebellion against cosmic and social orders, not by internal labyrinths of thought.

Shakespeare’s Hamlet shatters this model. In Hamlet, for the first time, the self becomes inward, reflexive, infinitely receding. The battlefield is no longer merely between man and fate, but within consciousness itself. Hamlet is suspended between thought and action, knowledge and paralysis. As he famously articulates:

"To be, or not to be, that is the question: / Whether ‘tis nobler in the mind to suffer / The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune, / Or to take arms against a sea of troubles, / And by opposing end them."

Here, existence is not simply endured or confronted; it is questioned from within. This inward turn inaugurates the modern self: a self divided, burdened by its own awareness, alienated from its own instincts. Harold Bloom captures this seismic shift when he declares: "Shakespeare, through Hamlet, invented us: we are the heirs to his invention of the human, for we are the first culture that has been defined not by its divine aspirations or civic destinies, but by its internal discontents, its self-questioning, its consciousness of consciousness itself."

In Hamlet, Shakespeare creates not just a character but a new category of being—an inward, reflexive creature for whom existence itself becomes problematic. This invention of psychological complexity in drama prefigures not only Freud’s discovery of the unconscious but the entire modern experience of identity as a fractured, self-aware construction.

A vivid early expression of this psychic inwardness appears in Hamlet's first soliloquy:

HAMLET:

O, that this too too solid flesh would melt,

Thaw and resolve itself into a dew;

Or that the Everlasting had not fix'd

His canon 'gainst self-slaughter! O God! O God!

How weary, stale, flat, and unprofitable

Seem to me all the uses of this world!"

There is so much packed into this (or any given Shakespeare) play’s initial act. Here, Hamlet articulates not simply grief, but a profound existential nausea. His desire for dissolution (“solid flesh would melt”) expresses a wish to escape the very burden of embodiment and identity. Freud would later read such suicidal desires not merely as personal weakness but as eruptions of the death drive—a fundamental, unconscious pull toward non-being. Hamlet’s horror at the world (“weary, stale, flat, and unprofitable”) mirrors Julia Kristeva’s notion of melancholia, where the loss is so absolute that symbolic meaning collapses. His alienation from "all the uses of this world" reveals a self whose links to external reality have frayed beyond repair.

The psychoanalytic revolution, beginning with Freud, codifies what Hamlet intuitively performs. Freud's discovery of the unconscious reveals that the self is not master of its own house. Instead, desire, repression, and conflict structure the inner life. In The Interpretation of Dreams, Freud reads Hamlet as a figure whose paralysis stems from unconscious guilt and identification with the object of his hatred. The hero's inability to act is not a flaw but a symptom: the eruption of repressed wishes and contradictions into the sphere of decision.

Jacques Lacan's reading of Hamlet builds upon this foundation by introducing the mirror stage. Lacan theorized that the "mirror stage" is a crucial moment in early childhood when a subject first identifies itself as an object within a symbolic order, and thus becomes alienated from any pure, unmediated sense of self. As Lacan puts it: "The mirror stage is a drama whose internal thrust is precipitated from insufficiency to anticipation—and which manufactures for the subject . . . the succession of phantasies that extends from a fragmented body-image to a form of its totality."

In Hamlet, the mirror stage is not confined to infancy: it returns in fractured form throughout Hamlet’s ordeal.

The scene in Gertrude's closet, where Hamlet confronts his mother and kills Polonius, is a descent into a shattered mirror. Hamlet projects rage and guilt onto the "mirror" of Gertrude's body, struggling not only with her perceived betrayal but with the collapse of the symbolic structures (family, law, duty) that once defined his identity. Gertrude's bewildered reflection of his fury confirms not coherence, but disintegration.

Another uncanny mirror surfaces in Hamlet's encounter with Yorick's skull. Holding the skull, Hamlet stares into the abject future of identity itself: decay, loss of face, oblivion. Here, Lacan's idea of the misrecognized self reasserts itself: the self Hamlet once thought he possessed—youthful, noble, singular—is revealed as merely provisional, subject to the inescapable decrepitude of all flesh. Lacan's words resonate: "In the fragmentation of the body, the ego discovers not a stable image but a precarious unity that threatens to devolve back into dismemberment."

As Lacan suggests, the death of Old Hamlet signifies more than personal grief: it signifies the rupture of the paternal metaphor that secures the symbolic order itself. Without the father’s name, the world slips into a morass of competing images and hollow ceremonies. Hamlet’s obsession with staging the play within the play (“The Mousetrap”) is a desperate attempt to restore meaning through theatrical self-recognition—a reassertion of the Law of the Father—but the attempt only redoubles uncertainty. Reality remains unmoored, truth slides into performance, and Hamlet’s self becomes increasingly spectral, divided, and elusive.

In ancient tragedy, suffering arises from external misrecognitions and divine curses; in modern tragedy, suffering arises from within, from the opacity of desire and the fragmentation of identity. Hamlet does not merely suffer; he interrogates his own suffering. He does not fall: he folds inward, spinning endlessly in the dark corridors of self-consciousness. In doing so, he transforms the very nature of tragedy—and inaugurates the unbearable condition we now call modernity.

VIII. Conclusion: Hamlet and the Modern Condition

Hamlet was not the first man to suffer, nor the first to act. He was the first to know he was suffering, to know he was acting—and to collapse under the burden of that knowledge.

Through Hamlet, Shakespeare inaugurates a new condition of being: fractured, reflexive, endlessly self-aware. Before philosophy had named it, before psychoanalysis had mapped it, Shakespeare had already staged it. In Hamlet’s mind, thought devours action; language unmoors reality; memory becomes a trap rather than a foundation. He thinks, therefore, he doubts. He doubts, therefore he delays. He delays, therefore he dies.

What Freud would call the unconscious, what Derrida would call différance, what Baudrillard would call hyperreality—Hamlet intuits first, without a theoretical scaffold to save him. His Denmark is no mere decaying state; it is the first broken mirror of modernity, where meanings slip their moorings and selves disintegrate under the weight of too much seeing.

To witness Hamlet is not to admire a relic of Renaissance genius. It is to see the future bleeding backward into the past: a world where grief breeds irony, action breeds doubt, and the stage becomes indistinguishable from the life it was meant to represent. Shakespeare does not hold the mirror up to nature—he shows us that the mirror itself is cracked, refracting every certainty into endless, shivering uncertainty.

Hamlet dies, but the world he discovers—the world of fractured selves, unstable meanings, and exhausted acts—does not. It is the world we inherit. It is the world we call our own.

Of course, Shakespeare’s creative trajectory is, and rightly so, highly contested, and there is no definitive chronology of his output; Garber’s model is simply one useful way of approaching it, particularly because it emphasizes the dynamic evolution of genre and tone rather than locking Shakespeare’s works into rigid categories.

The person behind this pen name has two degrees in theatre and wholeheartedly concurs with this analysis. Hamlet is a singularity that precedes the development of human thought which can explain its meaning. As you say, it is a unique tragedy that defies the conventions obeyed even by the same author in his other work. The blending of supernatural with psychological, epistemological with spiritual, and reason with passion offers conflict and tension at every level. Thank you for the engaging read—refreshing to see literary analysis is alive and well somewhere in the world.

Best essay on Shakespeare I have ever read on this platform, without par and easily digestible.