“All great novels are acts of memory, whether they know it or not.” — Susan Sontag

Introduction: Reading Vollman

The story begins with an absence, a distance: a critic, a reader, sometimes a novelist who, like many of Vollmann’s most stubborn readers, found himself adrift in the labyrinth of Europe Central (2005). Like the narrator in one of Vollmann’s strange meta-histories, I began to realize that reading Vollmann was less an ascent toward knowledge than a slow circling of an archive I could never quite penetrate. Not with this entry to his catalogue, at any rate.

Most readers come to Vollmann through fascination with the man himself, orbiting in the postmodern maximalist circles of authors including contemporaries such as Thomas Pynchon, Don DeLillo, and David Foster Wallace. My own path, on the other hand, mirrored the online wormholes of Cold War paranoia as an expat in Asia: from North Korea’s shadowy hermit kingdom to the Soviet terror that shaped the last century. What I sought was not clarity but atmosphere: a proper scaffolding of dread (masochistic though it may seem). And Vollmann—this encyclopedic American, this peculiar maximalist, this journalist-historian-ethnographer-novelist hybrid—offered a library disguised as a novel. His Atlas (Vollmann 1996) had felt like a passport; Europe Central was a dossier. It was not a novel I read; it was a novel I endured.

Sitting down to read Europe Central is like scaling a glacier with footnotes for crampons. I toggled between the hardcover, the Kindle, and an Audible narration while commuting across Hanoi, a teacher by day, an editor by night, a novelist in stray, exhausted hours. The book stretched across six months of lesson plans, grading, visa paperwork, and half-finished sentences. It hovered in my bag like a legal file, accusing and unfinished. Each page promised more than I could retain; each chapter dared me to start over. The book, if we follow the track of Vollmann’s own metaphors, is not an object of beauty but an object of weight. And yet the accumulation is the point. Vollman’s is a project that attempts to map conscience by overwhelming it. His method is clinical, documentarian, and genre-shifting. Some chapters (Shostakovich’s fugue-like inner monologues) enchant; others (the military chronicles of Andrey Vlasov) flatten. The reader must adjust expectations: to treat some chapters as opera, others as academic prose, others as fragments from a historian’s notebook.

When reading Gravity’s Rainbow (1973) over the global Covid-19 threat, I noticed what distinguished Pynchon’s maximalism from Wallace's for instance: it metabolizes disciplines sentence by sentence. Vollmann, by contrast, separates his genres into great, unbroken slabs. Pynchon’s chaos lives in the syntax; Vollmann’s knowledge builds a fortress. The reader—this reader—marveled from outside, never quite crossing the threshold.

In what follows, I want to explore Europe Central’s formal risks and ethical and narrative costs. Stefano Ercolino’s The Maximalist Novel (2014) provides a useful lens: maximalism’s hallmarks—length, encyclopedic scope, digressions—both amplify and dilute. Vollmann’s monumentality demands admiration, but leaves intimacy fractured. In this sense, his project is both necessary and alienating: a library pretending to be a novel, a novel pressing insistently against the limits of its form, interrogating what a novel can encompass, and at what cost.

Structure and Style: Narrative Disruption and the Ethics of Representation

The structure of Europe Central is fragmented, introducing a narrative design that foregrounds ethical representation and narrative fragmentation—two key themes that will shape the analysis that follows. Each chapter presents a different angle, a different narrator, or a different historical figure’s moral crisis. It's quite the mosaic and, for a time, the multiplicity exhilarated me. The chapters devoted to Dmitri Shostakovich—”wonder[ing] whether his silence will count as assent, or as defiance" were gripping, even moving. But others, like the extended sections on Andrey Vlasov, felt like I had wandered into a military history text. The voice flattened. The moral tension became subsumed under detail.

Here, Vollmann’s maximalism works both for and against him. His accumulation of data, stories, and moral portraits intends to overwhelm, to approximate the density of history itself. But in doing so, he risks turning the narrative into an archive. The novel’s pulse slackens under the weight of its knowledge.

This is not simply a matter of length. It’s a matter of rhythm, of how different modes are sequenced. Where Pynchon blurs aesthetics at the level of the sentence, Vollmann separates them by chapter. The result is a discontinuity of intimacy. Each shift in narrator or form pulls me out of the novel. The voice and context is often so drastically different that the narrative doesn’t propel; it rotates. It doesn’t invite me closer; it hands me another dossier.

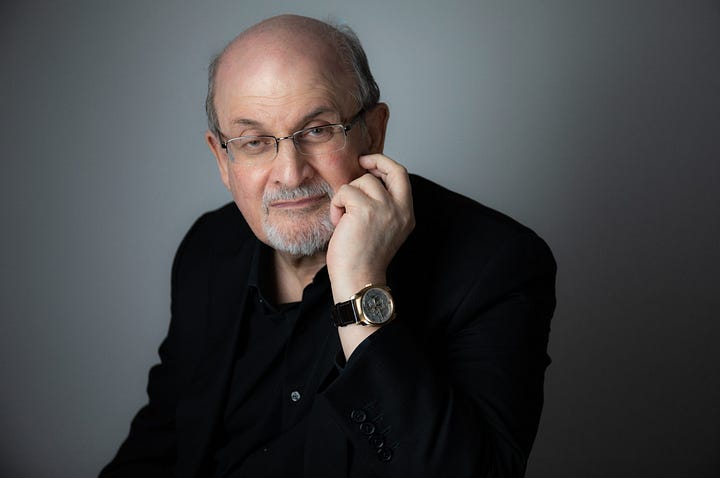

I kept returning to James Wood’s essay “Human, All Too Inhuman” (2000), a now-canonical critique of what he called the “hysterical realism” of contemporary fiction. In it, Wood diagnoses a shift away from emotional interiority and psychological realism, toward novels that are overburdened by structure, ideas, and stylistic display. Zadie Smith’s White Teeth (2000) comes in for harsh criticism, as does

and his mid-to-late career, including The Satanic Verses (1988)—which Wood sees as symptomatic of this turn. And to an extent, I share his concern. There is something in the tradition of the novel, rooted in the realism of Austen, Dickens, and Tolstoy, that should not be so easily abandoned. We risk losing the very thing fiction does best: charting the inner life, the quiet movements of moral thought, the drama of ordinary consciousness. But I part ways with Wood in several respects. Why throw the baby out with the bathwater? Rushie’s his work is not simply energetic or overdesigned—it’s mythic, plural, politically urgent, and (above all) brave. The maximalism of Midnight’s Children (1981) is not ornamental; it arises out of the fractured, polyglot condition of postcolonial identity. Vollmann, on the other hand, operates from a very different impulse. His maximalism is archival rather than effusive, documentarian rather than mythic. Europe Central (2005) does not dazzle; it burdens. Where Rushdie bends the novel toward storytelling as inheritance, Vollmann bends it toward testimony—as if the novel itself were an instrument of witness. In that sense, while Wood’s critique of hyperrealism lands forcefully, Vollmann doesn’t so much fall prey to it as he does push it to its breaking point.Perhaps Vollmann’s aim was not story but structure: a moral fugue, a historical tapestry, a zone of conscience. But then one must ask: what role does narrative play here? If the novel’s primary function is to compel, to carry, to create a rhythm of absorption, then Europe Central challenges that definition as far as time and patience can be had.

Inventory of Major Figures: History and Fiction

Part of what makes Europe Central remarkable, and difficult, is its use of real historical figures as characters. Dmitri Shostakovich emerges as the novel’s emotional and aesthetic center (only after 450 some odd pages): "Each note trembled between obedience and defiance," a line that captures his interiority and moral tension, providing textual evidence for the chapters' 'musical' quality: Vollmann fictionalizes his interior life with imagined inner monologues and speculative emotional landscapes, blending historical fact with invented moments of doubt and resolve. This approach echoes

’s embodiment of Monroe in Blonde (2000), where the real figure becomes a canvas for psychological projection, raising undecidable questions about the ethics of narrating real lives through fiction: a composer trapped between survival and artistic integrity, haunted by the possibility that every note betrays or resists.Andrey Vlasov, by contrast, reads colder: Vollmann fictionalizes his motivations and moral justifications, layering imagined introspection onto the historical record. A Soviet general who defected to the Nazis, his chapters feel like long military reports. Vollmann’s interest in betrayal, in shifting allegiances, finds a logical home in Vlasov’s story—but narratively, the sections feel distant, their intimacy buried beneath research.

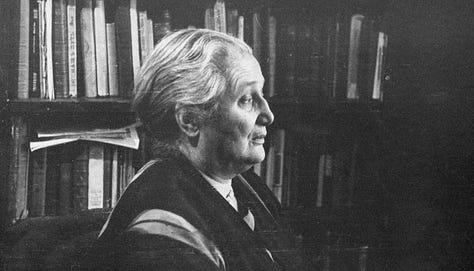

Käthe Kollwitz offers a quieter moral voice: Vollmann imagines private moments and interior reflections to humanize her, crafting scenes of solitude and ethical contemplation that are not drawn from direct historical record but from an interpretive imagination. Her presence in the novel feels like a necessary counterweight to the louder men around her—a portrait of ethical witness that feels earned, understated.

Other figures—Roman Karmen, Friedrich Paulus, Nadezhda Krupskaya, Anna Akhmatova—also appear.

Dmitri Shostakovich: Soviet composer; emotional/aesthetic center; moral struggle under Stalin.

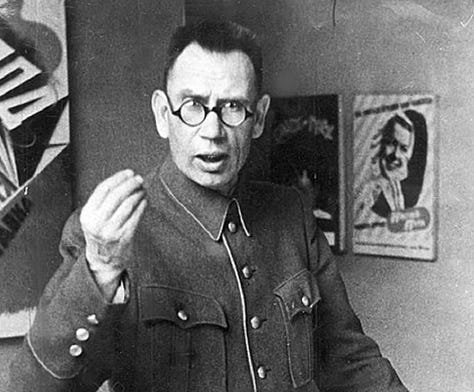

Andrey Vlasov: Soviet general turned Nazi defector; psychological portrait of betrayal and shifting loyalties.

Käthe Kollwitz: German artist; ethical witness; quiet moral counterweight.

Roman Karmen: Soviet filmmaker; symbol of propaganda’s complicity.

Friedrich Paulus: German Field Marshal; psychological portrait of defeat.

Nadezhda Krupskaya: Lenin’s widow, Soviet figure; historical witness caught in ideological shifts.

Anna Akhmatova: Russian poet; interior, poetic voice; testament to suffering.

With varying degrees of narrative warmth, each is fictionalized in distinct ways: Karmen depicted as a symbol of propaganda’s complicity, Paulus as a psychological portrait of defeat, Krupskaya as a historical witness caught in ideological shifts, and Akhmatova as an interior, poetic voice.

Some read as characters; others as sketches. Some chapters compelled me through their interiority; others felt like cold biographical case studies.

This unevenness, I suspect, is inherent to Vollmann’s method. By blending biography, history, fiction, and moral essay, he produces a novel whose very structure enacts the chaos of its content, shaped by the interplay of real and fictionalized events; Vollmann blurs the boundary between historical record and imaginative reconstruction intentionally, raising further ethical questions about how fiction represents truth and memory. But for the reader, that chaos can feel cumulative rather than integrative. I admired many parts, but I never felt I had grasped the whole.

This resistance to intimacy and resolution brought me to consider theorist Dominick LaCapra’s distinction between "acting out" and "working through" in historical trauma, inviting reflection on how his concepts position the reader ethically: are we implicated in this historical repetition, distanced as passive witnesses, or invited to judge and respond? between "acting out" and "working through" in historical trauma. As LaCapra writes: "Acting out is a repetition, a compulsive reliving of the past as if it were fully present, while working through involves a critical engagement that recognizes the past as past, allowing for a more ethical relationship to memory." In Europe Central, Vollmann’s repetitive moral structure—his return to betrayal, compromise, complicity—reads like a form of literary acting out. Each narrative loop reenacts historical trauma without resolving it, compelling the reader to dwell inside cycles of guilt and complicity. Unlike novels that aim for catharsis or closure, Vollmann’s project keeps the wound open. His fiction invites us not to master history, but to remain inside its irresolvable ethical tensions—a project that both parallels and complicates LaCapra’s framework.

In Writing History, Writing Trauma (2001), LaCapra argues that historical trauma challenges the very modes of narrating and representing the past. His thesis contends that historiography and cultural representation risk either compulsively repeating trauma ('acting out') or critically transforming it ('working through'), and that ethical representation requires recognizing the difference. Vollmann’s novel hovers between these modes, staging a form of literary “acting out” while simultaneously gesturing toward the impossibility of full narrative resolution.

The problem with the structure, hypercomplexity, and sheer length of Europe Central is that I do not feel consistently embodied enough within the narrative voice or the novel’s characters. It is not that Vollman is not excellent at writing character, but that—given the proclivity of his own voice’s dominance, with its intensive demands, digressions, and distance, therefore, from characters, which keeps Europe Central from succeeding as a work independent of its place in its architect’s bibliography.

Vollmann’s characters are not quite allegorical, but they often feel diagrammatic—figures positioned to map the crossings of art, ideology, and betrayal. This narrative scaffolding, while impressive, leaves little room for the spontaneous heat of feeling.

Take the following wall of text, unedited, not even the entirety of the paragraph it exists within:

They sent him on a tour of the occupied territories to drum up support. On 28.2.43 he arrived in Smolensk, where he spoke to the helots to great acclaim. (This man led the Fourth Mechanized against us at Lvov! Strik-Strikfeldt was explaining to everybody in a reverential voice.)—Russia must be independent, Vlasov kept saying.—Standing on a scorched and icy plinth which had once been burdened by a marble titan, he gazed down at his audience: shivering old men unfit for labor service, displaced peasant women in dark head-scarves, hungry office workers who’d been given Vlasov in lieu of a more expensive treat. To these people, who even yet hadn’t entirely abandoned their hope that the Germans might bring something good, his speech was electrifying. That one of their own—a famous general, no less—would be permitted to say anything at all, much less shout out a call for a RussoGerman alliance against Stalin, while Wehrmacht officers stood around smiling indulgently, was a sign that some middle path, however provisional and solitary, to the salvation which most of them after more than two decades of reeducation continued to cast in religious terms, might be more than a tragic figment. (We told you so! the old men whispered. What with the partisans, and Stalingrad, and that breakout at Leningrad, Adolf can’t be so arrogant anymore . . . ) Vlasov’s right arm rose high in salute to forthcoming Russian victories. Then he was photographed again, at attention in a file of Fascist officers each of whom was wearing shiny knee-length boots. He toured the newly reopened cathedral: Hitler the Liberator was bringing back religion! (But wily Stalin had begun reopening churches, too.) That night, he addressed a full house at the state theater, standing room only. As yet, his sponsors dared not permit him to broadcast on the radio. He propagandized here and there for three weeks, calling for volunteers. The first Vlasov Men already stood on parade for his inspection. (Let’s assume that he didn’t know about the Russian prisoners of war who were being gassed at Auschwitz, shot at Dachau and Buchenwald. At Smolensk alone the death rate was hundreds per day.) Insisting that he was no puppet, he quoted the old peasant proverb: A foreign coat never fits a Russian. (The uniform they’d fashioned for him was brown like a Storm Trooper’s.) To hostile questioners he replied: The Germans have begun to acknowledge their mistakes. And, after all, it’s just not realistic to hope to enslave almost two hundred million people . . . (You can’t hang all hundred and ninety million of us, Zoya had said.) His erstwhile captor General Lindemann came to congratulate him, and they clinked glasses. I must say, that was a riveting speech! These people believe in you, there’s no doubt about it . . . Frankly, I’m in despair, said Vlasov, for he’d just learned that the formations of Russian volunteers had all been broken up and distributed among German units. Upon my word now, what kind of thing is that for a military man to say? Just be patient a little longer, and Berlin will come around, I promise you! You see, it’s not just the war crimes, it’s the absurdity. How can your leadership fail to understand that by alienating the masses, they’re obstructing their own purpose? The German general sighed and said: Never mind, my dear fellow. The East and the West are two worlds, and they cannot understand each other. On his return to Berlin, the spring mud of the Reich now mouse-green like Hitler’s field jacket, he sent another memorandum admonishing the Reich government: The mass of the Russian population now look upon this conflict as a German war of conquest. (Zykov lost at solitaire and recited another stanza from Pushkin.) He advised his masters that even now it might still be possible to regain good relations with the people, so terribly had they suffered under Communism, but it was essential to make immediate changes in occupation policy.

To read Vollman is to read the pages of paragraphs composing his output that would—quite literally—reach your reading room ceiling. It is always read with this inundation of information. While it is very compelling in doses, it consistently loses me at about the 350-page mark, the length of the average novel published today, say, as I often find Vollman both spiritually exhausted and exhausting.

Conclusion

Reading Europe Central was an achievement for me, but not a pleasure. It challenged me, but it did not captivate me. I left it admiring the scale, the moral seriousness, the intellectual courage—but was also left with the feeling that the novel had denied me what I value most in fiction: the sense of living alongside characters, carried by a narrative rhythm that draws you forward.

If the novel began as an experiment in narrative intimacy—as Jane Austen’s framework of social consciousness, or even as Tolstoy’s epic poem of intertwined lives—then Europe Central represents a radical departure: a novel that seeks not intimacy but totality, not plot but archive. It is not a book I would binge, nor one I would revisit often. I’m grateful for its existence, grateful for Vollmann’s unfinishable library, but I remain, unfortunately, skeptical of its capacity to endure as an object of readerly love.

William T. Vollmann may well be the Herman Melville of our time—if not in public stature, then in artistic isolation, unfashionable ambition, and prophetic depth. Melville died largely unread, working as a customs inspector in New York; Vollmann, likewise, has lived for decades on the margins of literary celebrity, quietly assembling one of the most singular bodies of work in American letters. He has travelled where most would not dare: embedded with mujahideen fighters in Soviet-occupied Afghanistan for An Afghanistan Picture Show (1992), sleeping in alleyways and under freeways to research Whores for Gloria (1991), even entering Fukushima’s radioactive exclusion zone dressed in protective gear to write Into the Forbidden Zone (2011). The horror of such proximity is not only physical—it is existential. It is the horror of witnessing without the shield of metaphor. Vollmann does not write to elevate suffering into art; he writes to document its texture, its aftertaste, its residue. His books are not metaphors—they are thresholds.

If Moby-Dick (1851) was the first true encyclopedic novel, then Vollmann is Melville’s natural heir—less read, perhaps, but no less committed to capturing the full shape of human contradiction. It is now 174 years since Moby-Dick was published. And like Melville, Vollmann may remain largely unread in his time, his “information bricks” too heavy to circulate, too sprawling to be excerpted. This is the danger of writing for eternity. Canonical gambles do not pay off in decades; they take lifetimes, and sometimes more. Vollmann writes with the ghost of Melville on his shoulder—and the weight of twenty-first-century horror in his hands. He may never be fashionable, never be widely read. But for those of us who have lived with his books—not finished them, but lived with them—there is no mistaking the magnitude of his effort. His novels are not calls to action, but monuments to consciousness. If the novel still has a sacred function in our time, it is not entertainment—it is memory. And in that, I suppose, there is hope that Vollmann endures.

I have read very little of Vollman but understand that he contains multitudes...

quite a surprise to see my photo here, with my kitty Lilith! but "Blonde," though it appears maximalist is really much much truncated & selective; 1/1,000 th of a Vollman treatment of the same topic. thanks for this!---Joyce Carol Oates

Awesome review. It really does make me now want to start reading through his catalog. Curious how close Europe Central is to Gravity's Rainbow, as I've been trying to get to that level of experience as I've been going through Pynchon's other works (but none hit that threshold).