Paul Schrader’s First Reformed (2017) is haunted, above all, by the slow decay of conviction. With Ethan Hawke in the role of a tormented minister slowly unraveling in the face of ecological collapse, spiritual doubt, and moral inertia, First Reformed stages a contemporary reckoning with American religiosity. Its closest thematic sibling in recent literature is

’ A Book of American Martyrs (2017), a panoramic novel chronicling the lives of two men—an abortionist and the fundamentalist who murders him—and their children, who must survive the aftershocks of fanatical belief. Schrader’s film and Oates’s novel both depict a crisis of faith refracted through the lens of national trauma, charting the moment when inner despair hardens into extremism. In both, America is not simply a country but a theological battleground.What emerges from reading and watching these works together is a portrait of a culture saturated in righteousness and self-destruction. The Christian Left and Right—once distinct camps—blur under pressure. The trembling priest and the righteous gunman are closer than we’d like to admit. Both seek transcendence. Both find it in sacrifice.

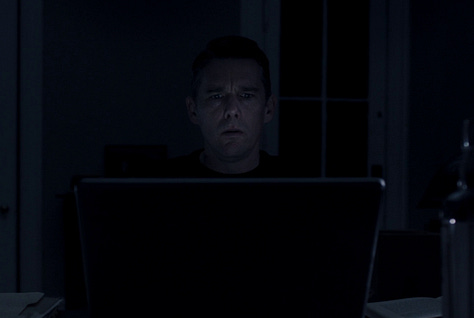

At the centre of First Reformed is Reverend Ernst Toller, played with ghostly restraint by Ethan Hawke. He is a man in retreat from the world, tending to a dwindling congregation in a cold, nearly empty Dutch Reformed church in upstate New York. The camera lingers on his solitude: writing in his journal, pouring whiskey into his Pepto-Bismol, walking stiffly through the winter air. Toller’s diary—spoken aloud in dry, confessional voiceover—guides us into his interior collapse. It is a slow death of hope, a sentence that becomes self-imposed. This use of the diary aligns with Schrader's early theoretical framework in his 1972 book Transcendental Style in Film (1972), where he writes that “the diary form replaces narrative development with spiritual stasis.”

Suitably, Schrader has Ethan Hawke’s Toller open the film with the words:

ERNST TOLLER: “I have decided to keep a journal. Not in a word program or digital file, but in longhand . . . When writing about oneself, one should show no mercy. I will keep this diary for one year. And at the end of that time, it will be destroyed. Shredded, then burnt. The experiment will be over.”

Over the course of the film, his journaling becomes both sacrament and self-annihilation.

Oates’s novel uses a different but related device: the panoramic interiority of her signature free-indirect style. The novel’s narration slips between the voices of Luther Dunphy, the fundamentalist assassin, and Augustus Voorhees, the slain abortion doctor. Their daughters, Dawn and Naomi, inherit the trauma and must reconstruct meaning from their fathers’ irreconcilable worldviews. The book’s strength lies in its multivocality—each character fiercely convinced, yet all fundamentally broken. If Schrader uses the diary to collapse time into one man’s unraveling, Oates uses multiple voices to capture the persistence of American fracture.

And yet the effect is strangely similar. Both the film and the novel are structured like suicide notes—slow burn elegies for a nation lost in ideology. “Will God forgive us for what we're doing to His creation?” Toller into the margins of his soul; Oates’ Dunphy believes God already has. The question is whether there is any grace left for those who remain.

In First Reformed, Toller’s radicalization is subtle and meticulously rendered. He meets Michael—a young environmental activist whose despair over climate change leads to talk of suicide. When Michael eventually kills himself, Toller inherits both his grief and his mission. He begins researching global warming, then writing furious sermons, then contemplating the use of violence to awaken a sleeping public. The final stages of his descent are cloaked in ritual: the donning of a suicide vest, the embrace of martyrdom.

He tells Michael, in a moment of pastoral clarity:

ERNST TOLLER: “Now Michael, I can promise you that whatever despair you feel about bringing a child into this world cannot equal the despair of taking a child from it.”

And later, to himself:

ERNST TOLLER: “Despair is a development of pride so great that it chooses one's certitude rather than admit God is more creative than we are.”

This progression mirrors the theological logic of Oates’s Luther Dunphy, whose murder of Dr. Voorhees is framed not as a crime but a crusade. Dunphy believes he is carrying out God’s will, and the chilling brilliance of Oates’s prose is that she never caricatures him. Rather, she invites us to witness the machinery of his belief—the scriptures, the community, the moments of self-doubt. Dunphy’s rhetoric of sacrifice is not unlike Toller’s in the final act of First Reformed: both see their death (and others’) as a necessary cost for a higher moral good.

But while Oates deconstructs this belief through the long lens of family trauma and intergenerational fallout, Schrader accelerates it into operatic climax. The final twenty minutes of First Reformed compress years of grief into a single day. Toller wraps himself in barbed wire, a modern crown of thorns. He prepares to explode himself at a church service attended by environmental criminals. But in the final moments, Schrader veers away from violence into mysticism. A kiss—long, ecstatic, possibly imagined—interrupts the ritual. Redemption, or hallucination? As Schrader noted in an interview with Film Comment, this ending is the “decisive action” followed by “transfiguration” in the transcendental style, where “the spiritual” is evoked through “the withholding of style until the final moment.”

This aesthetic structure also evokes the Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben’s notion of the “state of exception,” wherein normative moral order is suspended to authorize a new sovereign claim. Toller, like Luther Dunphy, steps outside civil law in the belief that divine law compels him. Their decisions are theological-political acts. Carl Schmitt, the theorist of political theology, would recognize in both characters the sovereign figure who “decides on the exception.” The suicide vest, the rifle, the church—all become sacred objects temporarily repurposed for judgment.

Both First Reformed and A Book of American Martyrs are stories of men undone by conviction—but the women in their orbits often bear the material consequences. Mary (Amanda Seyfried), the pregnant widow of the activist in First Reformed, becomes the quiet moral centre of the film. Her presence destabilizes Toller’s suicidal trajectory. Her body, as both vessel and symbol, becomes a kind of covenant he cannot desecrate. In one of the film’s most surreal moments, Mary and Toller lie together, floating through the cosmos in an act of shared breath and vision.

Toller speaks of Mary’s pregnancy with reverence:

ERNST TOLLER: “There's something growing inside Mary, something as alive as a tree, surely. As an endangered species. Something full of the beauty and mystery of nature.”

In Oates’s novel, it is the daughters—Naomi Voorhees and Dawn Dunphy—who carry the narrative’s emotional weight. Naomi, the intellectual, becomes more and more furiously skeptical of religion, seeking truth through secular language. Dawn, traumatized and silenced by her father's actions, becomes a reality television contestant and eventually a born-again Christian. Their lives are shaped by the men who tried to define righteousness. Both women reject and reinterpret that inheritance in their own ways, but their scars remain. Oates suggests that ideology, especially when fused with gendered violence, creates generational hauntings.

In an interview with LitHub, Oates remarked that writing Martyrs was her attempt to understand not only extremism but its fallout: “I was interested in how daughters and sons go on living after their fathers become symbols. They inherit not just the trauma but the spectacle.” It’s an insight parallels Schrader’s own, at the Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF), that First Reformed is a film about the impossible inheritance of guilt. Both works ask: how does one continue under the weight of a parent’s sacrifice—or delusion?

This is where the works diverge in form but align in substance: First Reformed offers a lyrical meditation on one man’s spiral into death or grace, while Martyrs insists on bearing witness to the full blast radius of male fanaticism. The novel’s 700 pages are necessary because the damage is diffuse and historical. Schrader’s film is a chamber piece. Oates’s is a gothic mural.

One of First Reformed’s most powerful visual motifs is that of decaying religious space. The titular church is a preserved artifact, mostly empty, funded by a nearby megachurch (Abundant Life), which is loud, impersonal, and corporate. Toller’s world is shrinking—he is surrounded by ruins. The film's cinematography, squarely framed and drained of colour, renders every hallway and pew like a tomb. The church is not a place of refuge, but a fossil of a belief system that no longer animates. This motif is quintessentially transcendental: what Schrader calls "the everyday" stage, where emptiness becomes the spiritual condition.

Similarly, in A Book of American Martyrs, space is deeply politicized. Abortion clinics, evangelical churches, suburban kitchens, courtroom pulpits—each one is freighted with moral conflict. Oates is attentive to the way American institutions become battlefields. Even the language of architecture becomes theological: the Voorhees clinic is described with both clinical precision and gothic unease, just as the courtroom becomes the site of false redemption and the bedroom becomes a confessional.

Both works understand that American Protestantism is inseparable from its geography. The roads are long, the houses spaced apart, the towns riddled with rot. Aesthetically, Schrader borrows from Bresson and Bergman, creating a purified landscape of moral silence. Oates—more baroque—floods her pages with density and contradiction. But both works culminate in a vision of sacred space as endangered habitat. The real apocalypse is spiritual. And it has already begun.

If, as Shrader writes, “transcendental style” in film delays emotion, suppresses narrative, and withholds catharsis to induce a spiritual crisis in the viewer. First Reformed is the purest expression of that theory he has ever achieved. The film’s stillness, its static compositions, and Hawke’s minimalistic performance all create a chamber of psychological reverberation. You are made to feel time. You are made to squirm in it. When the final gesture of the film—a sudden cut to black after the kiss—arrives, it does not offer relief. Only a question.

Oates, by contrast, does not delay emotion. She dives into it, tearing through layers of psychology and ideology with her trademark ferocity. A Book of American Martyrs is operatic not in silence, but in saturation. The novel is a courtroom, a confessional, a protest march, and a family scrapbook all at once. It does not simplify. It does not release. It demands judgment—and then recoils from it.

They are formally opposite but morally aligned. Both suggest that no one walks away clean. That America’s sickness lies not only in its politics, but in its soul.

Both Paul Schrader’s First Reformed and Joyce Carol Oates’s A Book of American Martyrs are works of theological realism. They ask what happens when the language of salvation is put under pressure—when the promises of grace, sacrifice, and righteousness become deadly. They are both deeply American in their suspicion of institutions and their reverence for the individual conscience, even as they expose the violence such reverence can breed.

In Schrader’s world, the man of God becomes a suicide bomber to shake the conscience of a poisoned world. In Oates’s, the servant of Christ murders a doctor to save unborn souls. In both, the line between faith and fanaticism is terrifyingly thin.

What remains is the question Mary asks in First Reformed, and that Oates echoes in her final pages: “How do we go on living in a world like this?” Neither story offers an easy answer. But they do offer the only thing harder than grace: witness.

Such a wonderful film that doesn’t seem to get as much attention as it deserves. And now you’ve made me want to pick up Joyce Carol Oates’ book which I was not familiar with. Thanks for sharing !

Excellent essay once again, you make me compelled to read and see the movies mentioned.