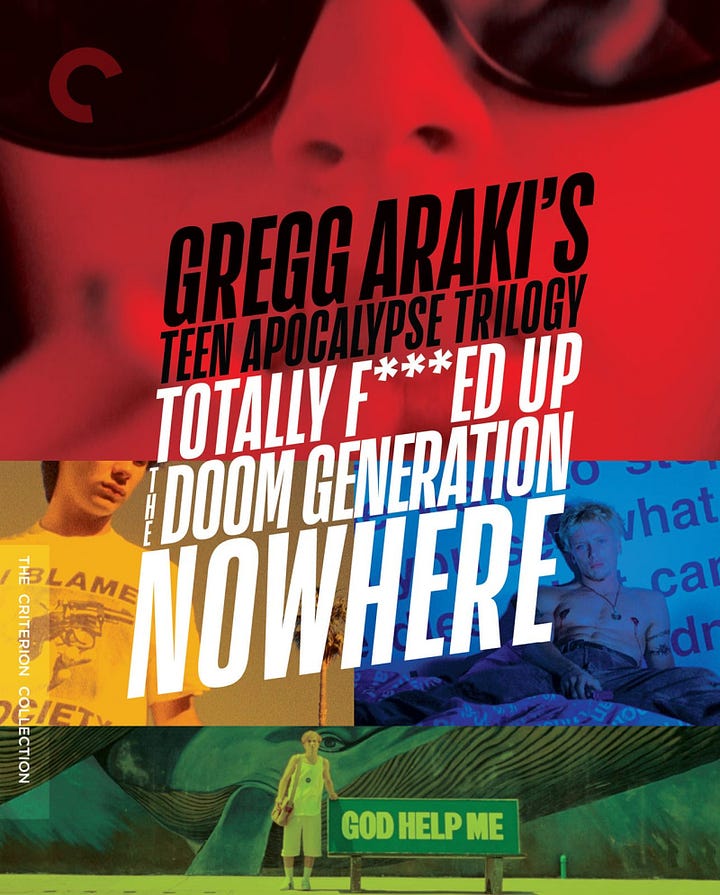

At first glance, pairing Byung-Chul Han’s The Burnout Society with Gregg Araki’s Teenage Apocalypse Trilogy—Totally F**ed Up* (1993), The Doom Generation (1995), and Nowhere (1997)—may seem like an odd intellectual exercise. Han’s slim but piercing philosophical treatise diagnoses the modern subject as trapped in a cycle of self-exploitation driven not by external oppression but by an internalized demand for productivity. Araki’s films, by contrast, are chaotic, hyper-stylized fever dreams, drenched in neon nihilism and the alienation of queer youth on the fringes of a disintegrating world. Yet, the overlap emerges in the exhaustion and breakdown of these characters: their hedonism is not liberatory but desperate, their rebellion not against a clear authoritarian force but against a vague, omnipresent pressure to exist “correctly” in a collapsing system.

Han’s critique of a society ruled by self-imposed overexertion therefore finds an unlikely but fitting mirror in Araki’s burned-out, disillusioned teens, whose aimless wanderings and self-destructive spirals reflect an existential fatigue that feels eerily contemporary. What might seem like an odd comparative analysis instead reveals the deep structural anxieties binding both Han’s philosophy and Araki’s cinema—the exhaustion of autonomy, the impossibility of true escape, and the slow erosion of identity under the weight of a world that demands everything yet offers nothing.

Born in 1959 in Los Angeles to Japanese-American parents, Gregg Araki emerged in the late 1980s as a defining voice in independent queer cinema. A self-described outsider, Araki operated then much as he does today: on the fringes of Hollywood, making films on shoestring budgets that pulse with raw, anarchic energy. His early work, particularly The Living End (1992), helped set the tone for what would become his signature style: a mix of apocalyptic dread, deadpan absurdity, and hypersexualized youth lost in the wasteland of American culture. Much like Byung-Chul Han—who grew up in Seoul before moving to Germany, where he cultivated his critique of contemporary neoliberalism—Araki’s work is shaped by an outsider’s perspective, both geographically and philosophically. Han, a reclusive thinker, often describes modern life as an isolating system where individuals, convinced of their own autonomy, unwittingly self-exploit. Araki, meanwhile, captures the lived experience of that isolation in his films, presenting characters who are estranged from both societal norms and themselves.

Araki has spoken about this sense of existential detachment, particularly in relation to the modern world's overwhelming demands. “We live in this very isolated world,” he says in this interview, “where technology is supposed to bring us closer together, but in a way, it makes us more alone. People are trapped in these little boxes, in their own curated versions of themselves.” The statement echoes Han’s argument that digital culture and the gig economy have produced a burnout society, one where people compulsively perform and produce, yet feel increasingly exhausted and empty. Araki’s Teenage Apocalypse Trilogy plays out this crisis through exaggerated, hyperreal aesthetics: its characters desperately seek meaning through sex, violence, and destruction, yet remain fundamentally untethered, much like the modern subjects Han describes—trapped in a system that paradoxically alienates them the more they participate in it:

Excess positivity, which manifests itself as overproduction, overachievement, and overcommunication, leads to self-exploitation. The tired self, worn out by this compulsion, loses the ability to pause, to reflect, and ultimately, to truly be . . . We owe the cultural achievements of humanity—which include philosophy—to deep, contemplative attention. Culture presumes an environment in which deep attention is possible. Increasingly, such immersive reflection is being displaced by an entirely different form of attention: hyperattention. A rash change of focus between different tasks, sources of information, and processes characterizes this scattered mode of awareness. Since it also has a low tolerance for boredom, it does not admit the profound idleness that benefits the creative process.

Byung-Chul Han’s rather troubling conception of “excess positivity” in The Burnout Society refers to the way modern neoliberal societies no longer rely on external oppression to control individuals but instead drive individuals to overwork and overproduce through—significantly, self-imposed pressure. Unlike past disciplinary societies, structured around prohibitions and restrictions, contemporary culture operates through an ideology of limitless potential—one that tells individuals they can and should do more, achieve more, and optimize every aspect of their existence. The result is a state where individuals push themselves beyond their limits, leading to exhaustion, anxiety, and eventual collapse. Han describes this as a condition where “the tired self, worn out by this compulsion, loses the ability to pause, to reflect, and ultimately, to truly be.” His critique of modern burnout aligns eerily well with Araki’s vision of young lives collapsing under the weight of their own accelerated nihilism.

Andy, played by James Duval in Totally F**ed Up*, embodies this exhaustion most explicitly. Sensitive and yearning for love, Andy finds winds himself up in cycle of rejection and disappointment. His burnout is not from work in the traditional sense, but from the emotional toll of constantly searching for connection in a world that seems designed to alienate him. Like the modern subject Han describes, Andy’s exhaustion is not just physical but existential—his crisis is one of being rather than simply doing. He is caught in an affective economy where relationships, self-worth, and even queerness itself feel commodified, his pain heightened by the knowledge that he is supposed to be free, supposed to be thriving.

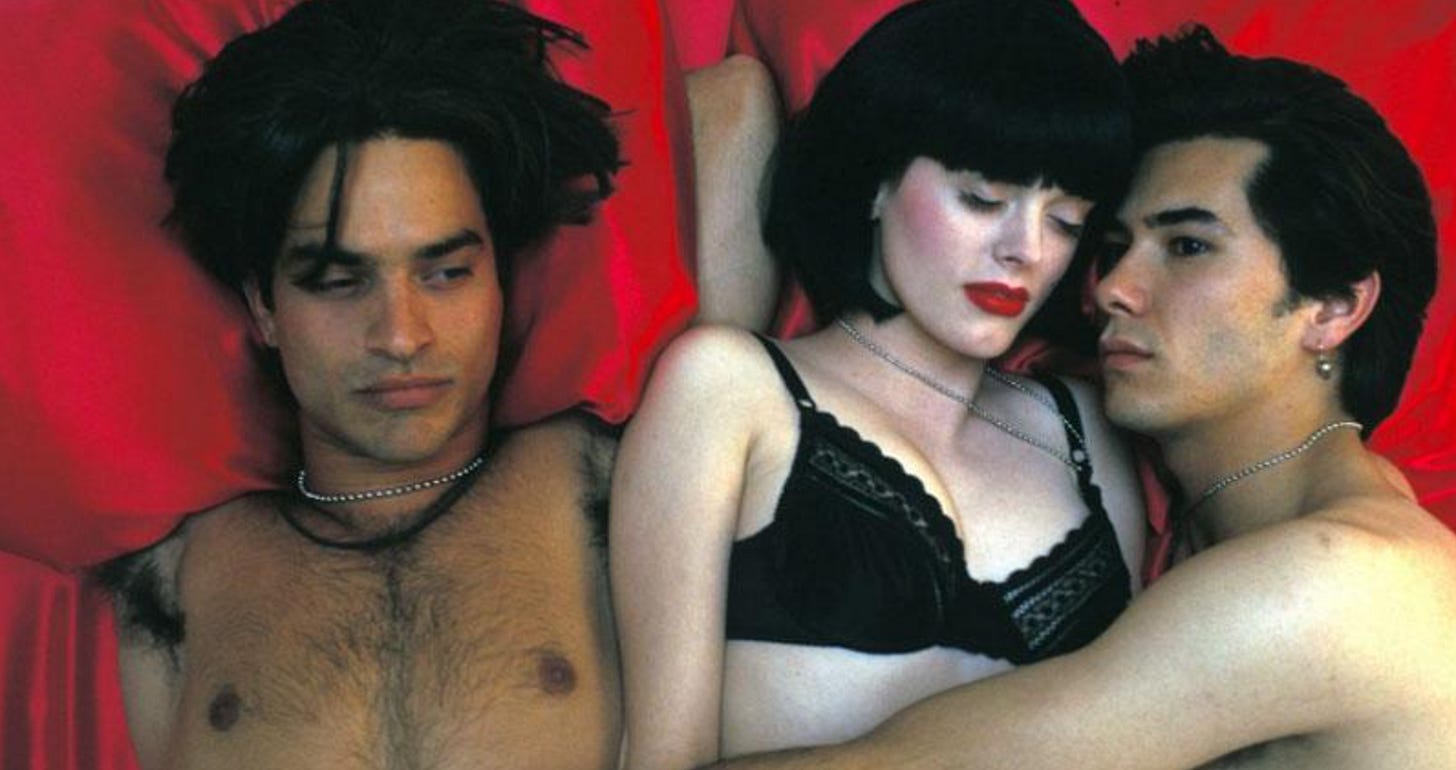

In The Doom Generation, Johnathan Schaech’s Xavier and Rose McGowan’s Amy Blue find themselves drifting through a hyperviolent, desensitized America, where nothing feels real but everything feels urgent. They begin as jaded but relatively controlled, only to spiral into a frenzy of sex and brutality that escalates beyond their grasp. Han suggests that burnout is not always a slow fade—it can reach a point of rupture, where the self implodes from the accumulated strain of overexertion. Xavier and Amy embody this collapse. Their rebellion against the world is less about genuine resistance and more about the frantic search for something to matter. The more they push against the edges of experience, the more those edges dissolve, leaving behind only an accelerating void. Their trajectory mirrors the burnout worker who, after years of relentless self-optimization, finally snaps—not in quiet resignation, but in violent desperation.

James Duval’s Dark Smith in Nowhere represents the endpoint of Han’s burnout subject—the complete dissolution of meaning and selfhood. If Han’s argument is that excess positivity leaves people unable to truly pause or exist outside the logic of self-production, then Dark is its ultimate casualty. He moves through a world that looks like reality but feels artificial, his experiences hyperreal yet emotionally vacant. He seeks stimulation—parties, drugs, sex—but nothing satisfies him, because the burnout subject does not experience satisfaction, only the compulsion to continue. Han’s assertion that “the ability to stop is what distinguishes life from mere survival” finds its perfect cinematic expression in Nowhere, where Dark exists in a state of perpetual forward motion, unable to stop even as reality itself unravels around him.

The Doom Generation nonetheless stands as the definitive Gregg Araki film for me—much in the way that I regard Pulp Fiction (1994) as “definitive Tarantino,” regardless of minor personal struggles with the simple fact it is so widely regarded as such. Araki’s later film, Mysterious Skin (2007)—far more mature and earnest in its intent—is his singular greatest achievement, but The Doom Generation is a career centerpiece, arguably the film that most fully realizes his aesthetic, thematic, and philosophical concerns. Arriving drenched in a feverish, hyper-saturated color palette that heightens its surreal, nightmarish energy, every frame is soaked in neon reds, deep blues, sickly greens, as though the film itself is bleeding under the pressure of its own excess.

What makes The Doom Generation so uniquely powerful is its ability to balance this relentless aesthetic with a structure that feels, at first, a lot like a hangout movie—only to twist itself into an inescapable horror film. The first half is loose, even fun: Amy, Xavier, and Jordan (James Duval) drift from convenience stores to motel rooms, exchanging nihilistic banter, engaging in impulsive sex, and laughing in the face of escalating violence. There’s a casual absurdity to it all, a playfulness that gives the film a kind of hypnotic charm. But as it progresses, the humor curdles, the road movie escapism collapses into claustrophobic doom, and the audience is trapped alongside the characters in a world that no longer offers even the illusion of escape. The balance between levity and horror, comedy and brutality, is what makes it so rewatchable—it’s a film constantly shifting under its own weight, revealing new layers of cynicism and despair with each viewing.

If Han’s argument is that neoliberalism has turned individuals into self-exploiting machines, caught in cycles of compulsive labor and self-destruction, The Doom Generation applies the same idea to the collapse of identity under a hyperviolent, hypersexualized, and relentlessly media-saturated America. The characters are stripped of agency, and punished for existing in a world that thrives on consumption and annihilation. By the time the film reaches its brutal, gut-wrenching climax, there’s no ambiguity left—this isn’t just teenage apocalypse for the sake of it. It’s a vision of inescapable, systemic doom, a world where the only real choice is how long you can pretend it’s all just a joke.

The Doom Generation (1995) follows Amy Blue (Rose McGowan), her boyfriend Jordan White (James Duval), and the mysterious drifter Xavier Red (Johnathan Schaech). Amy and Jordan, a disaffected teenage couple, encounter Xavier after a chance meeting at a convenience store robbery culminating in a talking severed head. As the story makes its way across the news, drawn in by his seductive and chaotic energy, they reluctantly allow him to join them. As they travel through a neon-drenched, hyper-stylized America, their journey becomes increasingly surreal, punctuated by explosive bursts of violence, bizarre encounters with deranged locals, and an intensifying sexual tension between the three.

Beginning with a dark humor and a playful nihilism, but as they leave behind a trail of blood and destruction, the tone shifts into something more nightmarish. They are pursued by an array of cartoonishly menacing antagonists, each more grotesque than the last, culminating in a brutal, deeply disturbing climax where Jordan and Xavier are attacked by Neo-Nazi, homophobic assailants in a scene of explicit, senseless violence that shatters whatever ironic detachment the film had maintained. Amy and Xavier, lone survivors of the attack, drive off, fates as uncertain as the world they leave behind.

The Doom Generation takes its characters on a journey that begins as reckless adventure but descends into Araki’s bleakest vision of America as a landscape of violence, repression, and moral decay. When a cashier sneers: “That'll be $6.66,” the moment is played for comedy, but it is also an omen.

Araki saturates The Doom Generation with symbols of this moral decay. Every roadside stop and lurid neon sign pulses with a sense of impending doom. Convenience stores become battlegrounds of mindless consumerism and sudden violence, their harsh fluorescents illuminating the grotesque nature of American excess. Fast food wrappers and motel room detritus litter the landscape, reinforcing the sense of transience and disposability that defines both objects and people in this world. The trio’s encounters with hostile strangers—xenophobic gas station attendants, sleazy motel clerks, violent punks. Cigarette packs are printed in black with white skulls. The omnipresence of television static and garish advertisements, moreover, suggests a culture driven by artificial stimulation, its citizens desensitized to both pleasure and suffering, culminating in the film’s final, unchecked hatred, revealing the true rot at the heart of this world—where transgression is punished, desire is met with brutality, and the veneer of ironic detachment can no longer protect anyone from the consequences of being alive in a dying system.

“Today’s society”—writes Han in The Burnout Society—“is no longer Foucault’s disciplinary world of hospitals, madhouses, prisons, barracks, and factories”:

It has long been replaced by another regime, namely a society of fitness studios, office towers, banks, airports, shopping malls, and genetic laboratories. Twenty-first-century society is no longer a disciplinary society, but rather an achievement society [Leistungsgesellschaft] . . . Disciplinary society is a society of negativity. It is defined by the negativity of prohibition. The negative modal verb that governs it is May Not. By the same token, the negativity of compulsion adheres to Should.

Achievement society, more and more, is in the process of discarding negativity . . . Unlimited Can is the positive modal verb of achievement society. Its plural form—the affirmation, “Yes, we can”—epitomizes achievement society’s positive orientation. Prohibitions, commandments, and the law are replaced by projects, initiatives, and motivation. Disciplinary society is still governed by no. Its negativity produces madmen and criminals. In contrast, achievement society creates depressives and losers.

The trio’s nihilism is a response to a world that has already cast them out. They are neither striving nor ambitious; they wander through a wasteland where everything is disposable, including themselves. Jordan, Xavier, and Amy’s passive self-destruction reflects Han’s idea that, in a society obsessed with achievement, those who refuse to play the game are treated as expendable. The violence against them is a logical extension of their refusal to integrate into a system that only values success through compliance.

In many ways, the ideas explored by Byung-Chul Han and Gregg Araki find their culmination in the David Fincher adaption of

’s Fight Club (1999):TYLER DURDEN: Man, I see in fight club the strongest and smartest men who've ever lived. I see all this potential, and I see squandering. God damn it, an entire generation pumping gas, waiting tables; slaves with white collars. Advertising has us chasing cars and clothes, working jobs we hate so we can buy shit we don't need. We're the middle children of history, man. No purpose or place. We have no Great War. No Great Depression. Our Great War's a spiritual war . . . Our Great Depression is our lives. We've all been raised on television to believe that one day we'd all be millionaires, and movie gods, and rock stars. But we won't. And we're slowly learning that fact. And we're very, very pissed off.

Alongside Araki’s Teenage Apocalypse Trilogy, Fight Club’s resonance comes from its unflinching articulation of the same crisis Han describes in The Burnout Society—a generation caught between the illusion of limitless potential and the crushing realization that this potential will never be fulfilled. The rage in Tyler’s words is the same latent fury that simmers beneath The Doom Generation—a generation raised on media fantasies of power and success, only to be confronted with a meaningless, exploitative reality. The way these films continue to find new audiences reflects an ongoing connection to Han’s critique: people return to these works not just because they are provocative or stylish, but because they capture a deep existential exhaustion, an exhaustion that has only intensified in the decades since their release. If Araki’s films were the burned-out nihilistic shrug of the ‘90s, Fight Club was its last desperate howl, articulating the desire to break free from a system that thrives on self-exploitation—only to fall into another cycle of destruction. In both Han’s diagnosis and these films, the great tragedy remains the same: the more we fight, the more the system finds a way to absorb our resistance, repackaging it into yet another product to be consumed.

Man this is such an intellectual deep dive, real hard work critical analysis you and Sophie in a league on yall own as far as I can tell.

I can only imagine how much work you put into this, Brock. Funnily enough, I have The Burnout Society in my TBR list - I’m going to move it up a notch or two, after reading this.

The Araki trilogy, which I’d heard of but not seen, sounds like something I really want to watch, not least for the cinematography you describe. Visual artistry is something I really appreciate in films (movies!).

I’m so glad I read this - thank you for writing such an informative article.