Blonde and the Myth of Marilyn: A Literary Reckoning

’ Blonde (2000) has been a point of literary debate since its turn-of-the-century publication—an unsettling reimagining of Marilyn Monroe’s myth that I initially dismissed (Joyce Carol Oates’ novel and Andrew Dominik’s film)—as just another take on celebrity’s dark underbelly. That assumption was challenged when I began to take a closer look at Monroe’s cinematic journey, sparking in me a reevaluation of her artistic merit. Critics have weighed in on the controversies surrounding her myth, with voices in The New Yorker and Variety lambasting the recent film adaptation as “a disjointed fever dream of aesthetic excess” and “a hollow, self-indulgent spectacle that betrays the tragic complexity of its subject.” Similarly, Manohla Dargis, writing for The New York Times, damned the film, and director Andrew Dominik’s approach to the material, characterizing him as Monroe’s ultimate victimizer:Given all the indignities and horrors that Marilyn Monroe endured during her 36 years—her family tragedies, paternal absence, maternal abuse, time in an orphanage, time in foster homes, spells of poverty, unworthy film roles, insults about her intelligence, struggles with mental illness, problems with substance abuse, sexual assault, the slavering attention of insatiable fans—it is a relief that she didn’t have to suffer through the vulgarities of Blonde, the latest necrophiliac entertainment to exploit her. Hollywood has always eaten its own, including its dead.

Yet hasn’t it always been so? Dargis’ critique of Blonde rests on the premise that Andrew Dominik has uniquely violated Marilyn Monroe’s legacy, reducing her to a tragic victim and indulging in an exploitative gaze that she herself suffered under in life. Yet the charge of “necrophiliac entertainment” overlooks a central, inescapable truth: Hollywood has always eaten its own, including its dead. And not just Hollywood—the entire machinery of American celebrity functions as a self-consuming ouroboros, feeding on myth, scandal, and the fevered projections of an audience eager to mold its icons into whatever shape best suits the collective fantasy. The vulgarity of Blonde is not a violation of Monroe’s image—it is its inevitable continuation.

To lament Monroe’s reduction to a beautiful victim is to misunderstand the foundation of Hollywood mythology itself, a mythology that thrives on desecration, as much—if not more—than it does reverence. Kenneth Anger’s Hollywood Babylon (1959) revealed this decades ago, peeling back the industry’s gilded façade to expose the sex, drugs, and self-destruction rotting underneath. Anger’s portraits of dead starlets and ruined leading men weren’t objective accounts of history; they were legends, exaggerated, lurid, shaped by their own excesses. Monroe, like all Hollywood saints, was made to be sacrificed at the altar of spectacle—both in life and in death. Eve Babitz understood this too. Her Los Angeles was a city of golden bodies thrown onto the pyre of fame, a place where sex and self-annihilation were part of the game, where every woman who made it past the studio gates was expected to strip herself down for the camera, in one way or another.

Dargis’ argument further assumes that a more refined and respectful film would somehow redeem her memory. But why should that be the standard? Blonde operates within the lineage of American mythmaking—one that has always required its icons to be destroyed in order to be reborn. This is not just Monroe’s fate, but the fate of every major star who became more than a person, who turned into a symbol. Monroe’s genius, her artistry, and her intelligence exist in her films, untouched, unerasable. Blonde does not overwrite them; it simply takes part in the same brutal tradition that made her a legend in the first place.

To be clear, however, make no mistake here: my focus in this review is on the Joyce Carol Oates novel, not the controversial 2020 film.

At its core, Blonde is a glittering, hallucinatory exploration of celebrity—a literary kaleidoscope that refracts the dazzling promise and inevitable curse of fame. Oates reimagines Marilyn Monroe’s beginnings from the orphan, Norma Jeane. Born Norma Jeane Mortenson on June 1, 1926, in Los Angeles, Monroe’s early life was defined by abandonment and instability. Her mother, Gladys Pearl Baker—plagued by mental illness and unable to provide a nurturing environment—was largely absent during these formative years, while her father had left. Shuffled between foster homes and an orphanage, Norma Jeane’s formative experiences were marked by a deep-seated yearning for the love and security that remained forever elusive.

In Blonde, these well-documented biographical facts are transmuted into myth. The Dickensian cruelty of her early years becomes not only a personal tragedy but also a metaphor for the relentless exploitation and disintegration of individual identity in the service of celebrity. The narrative’s glittery, fragmented cadence mirrors the psychological shattering of a girl whose inherent vulnerability is both exploited and exalted—a duality that would come to define her transformation into an icon.

Following the brutality of her earliest years—nearly killed by her mentally plagued mother, then put through the L.A. orphan and foster care systems, Norma Jeane’s tentative steps into Hollywood were marked by both promise and peril. Oates charts this transition with a narrative as fractured and luminous as the star it foretells:

Through the narrow window beneath the eaves, how many miles away she could not calculate, if she stood on the bed assigned to her (barefoot, in her nightgown, in the night), she saw the pulsing-neon lights of the RKO Motion Pictures tower in Hollywood:

RKO RKO RKO

Someday.

Who had brought her to this place the child could not recall. There were no distinct faces in her memory, and no names. For many days she was mute. Her throat was raw and parched as if she’d been forced to inhale fire. She could not eat without gagging and often vomiting. She was sickly-looking and sick. She was hoping to die. She was mature enough to articulate that wish: I am so ashamed, nobody wants me, I want to die. She was not mature enough to comprehend the rage of such a wish. Nor the ecstasy of madness such rage would one day stoke, a madness of ambition to revenge herself upon the world by conquering it, somehow, anyhow—however any “world” is “conquered” by any mere individual, and that individual female, parentless, isolated, and seemingly of as much intrinsic worth as a solitary insect amid a teeming mass of insects. Yet I will make you all love me and I will punish myself to spite your love was not then Norma Jeane’s threat, for she knew herself, despite the wound in her soul, lucky to have been brought to this place and not scalded to death or burned alive by her raging mother in the bungalow at 828 Highland Avenue.

This passage casts Norma Jeane as a lost child in as vast and indifferent a world as those of Oliver Twist (1838) or David Copperfield (1950). The pulsing neon of the RKO tower—RKO RKO RKO—mirrors, of course, Dickens’ orphaned protagonists’ glimpses of privilege from afar, tantalized by a future that feels both inevitable and unattainable. Oates layers this with raw sentimentality: mute and fevered, Norma Jeane articulates her wish to die without grasping the full force of her despair, a structure Dickens often employs—children suffering without yet understanding their fates. Most striking, however, is the transformation of pain into ambition; her unformed threat—“I will make you all love me and I will punish myself to spite your love.” Here, perhaps, the star, according to Oates, is born.

At sixteen, Norma Jean married James Dougherty, a local police officer—anonymized in the novel as “Bucky Glazer” to escape the orphanage system—until he leaves for the war against Japan and does not return. Dougherty seems to have been spared much of the public scrutiny imposed on the other lovers of Marilyn Monroe and his role in Monroe’s life remains the same—a figure of early, fleeting stability who ultimately belonged to a different life than the one she was destined for.

According to Oates’ telling, Monroe’s entry into Hollywood unfolds through her association with Cass Chaplin (son of the effectively politically “exiled” Charlie Chaplin, as readers of our Limelight (1952) discussion will recall)—a charismatic figure who immediately recognizes her raw magnetism at a time when the studio system is ravenous for new blood, new flesh. Cass and his lover Eddy G aren’t just gatekeepers; they assume the role of lovers, compelling Norma Jeane to embrace an identity that is as volatile as it is radiant.

Their connection—at once tender and tumultuous—becomes the fire from which the icon of Marilyn Monroe is forged. As the narrative shifts from the ghosts of her past to the dawning of her career, her evolution into Marilyn is not depicted as a singular triumph but as an ongoing, hallucinatory negotiation between self-reinvention and the crushing demands of a system eager to erase the individual in favour of the product. We see studio contracts pile up, relentless public scrutiny tightening its grip, and the ever-present pressure to conform at every step toward stardom—both a leap into glamour and a surrender of self.

In Blonde, Joyce Carol Oates presents a world in which identity is both inherited and obliterated, where the children of Hollywood’s greatest icons live in the shadows of legacies they had no hand in shaping.

So that’s Chaplin’s son! And little Lita’s!—and then failed to show up. He would not apologize afterward or even explain himself, and Norma Jeane would find herself apologizing to him for her own hurt and anxiety. He’d told her that being Charlie Chaplin’s son was a curse that others stupidly wished to believe must be a blessing—“Like it’s a fairy tale, and I’m the King’s son.” He’d told her that the much-beloved Little Tramp was a vicious egoist who despised children, especially his own; he hadn’t allowed his teenage wife to name their son for a full year after his birth, out of a superstitious dread of sharing his name with anyone, even his flesh-and-blood son! He’d told Norma Jeane that Chaplin divorced Little Lita after two years and disowned and disinherited him, Charlie Chaplin, Jr., because he wanted only the adulation of strangers, not the intimate love of a family. “As soon as I was born, I was posthumous. For if your father wishes you not to exist, you have no legitimate right to exist.”

I find the passage above a devastating reflection on both lineage and the myth of inheritance, voiced by Charlie Chaplin Jr. (“Cass”), the son of the legendary silent film star. His bitterness is palpable—he rejects the assumption that being the son of a global icon is a blessing, instead framing it as a kind of curse. His father, the beloved Little Tramp, is stripped of his sentimental mystique, revealed instead as a “vicious egoist” who hoarded admiration from strangers while rejecting intimacy from his own children. His superstition—refusing to name his son for a full year—becomes a grotesque metaphor for disinheritance, as if to name the child would be to acknowledge him, to accept responsibility for his existence.

Oates layers this with another reference invoking Nabokov’s infamous heroine through the mention of “Little Lita.” Lolita (1955) is, at its core, a novel about the destruction of innocence, about a girl stripped of her autonomy and reshaped through the desires of others. In Blonde, the parallel is unmistakable: Norma Jeane, like Lolita, is never allowed to exist as a full person—only as a reflection of what men want her to be. Her relationships with men like Chaplin Jr. and Eddy G are defined by power imbalances and inevitable betrayals. The fact that she finds herself apologizing to Chaplin Jr. for his cruelty is another painful echo of Lolita’s own self-effacement, her suffering internalized so deeply that she sees herself as the one at fault.

But Chaplin Jr.’s story is not just his own—it is also a warning, a mirror held up to Norma Jeane’s own trajectory. If he was “posthumous” from birth, doomed by his father’s rejection, then what does that say about Marilyn Monroe, whose very existence was shaped by absence and neglect? Like Chaplin Jr., she is the offspring of a legend, but one who will never be able to claim a real, stable identity of her own. In Hollywood, names are everything, but they do not belong to those who bear them. Chaplin’s son was denied his father’s name; Norma Jeane was forced to surrender hers, reborn as Marilyn Monroe. Neither could escape the machine that had already dictated their destinies.

This, ultimately, is how Hollywood destroys its heroes. Not through dramatic scandal alone, but through the slow, grinding erasure of selfhood. Chaplin Jr.’s father belonged to the world, and so he had no father at all. Monroe belonged to the screen, and so she could never fully belong to herself. Oates does not simply document their suffering—she transforms it into an archetype, an American tragedy where the children of legends are sacrificed to preserve the illusions their parents created.

With them comes her earliest brush with Hollywood, her tentative steps into stardom, and the shaping of her identity as something more than the orphaned girl seeking a place in the world. The Asphalt Jungle (1950), Don’t Bother to Knock (1952) and Niagara (1953) mark this era: films that, in their own way, recognize the undercurrent of unease in her screen presence, her ability to embody both vulnerability and something more volatile beneath the surface.

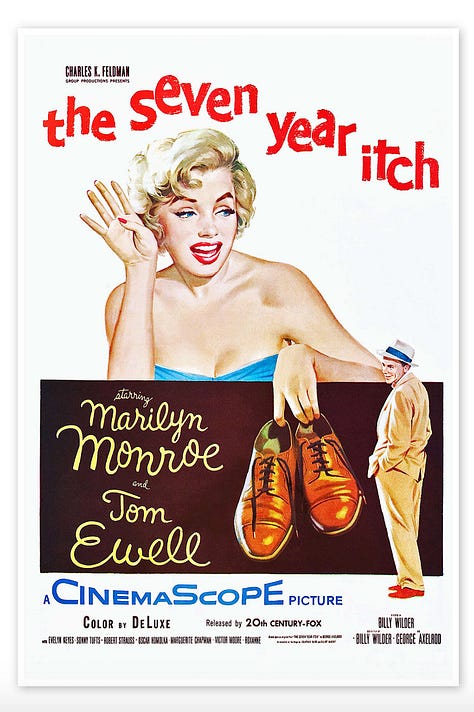

The second phase of her career begins with “The Athlete,” as Oates calls him—a figure whose presence heralds Monroe’s true ascent into pop-culture immortality. This is Joe DiMaggio, the baseball legend, the national hero, the American Dream incarnate. At the time of their meeting, DiMaggio is already a myth in his own right, having led the Yankees to nine World Series championships, his stoic masculinity enshrined in the public consciousness. Monroe, with The Seven Year Itch (1955) and Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (1953) on the table, is Hollywood’s most luminous blonde. Their union is, in the eyes of the public, a perfect symmetry of all-American glamour: the great athlete and the screen siren. Yet this phase of her life is also fraught with control, jealousy, and the clash between personal desire and public expectation. DiMaggio, uncomfortable with her growing sex symbol status, is unable to reconcile her on-screen persona with the woman he wants behind closed doors. The marriage collapses under the pressures of Norma’s fame in the press, ever-hungry for scandal, devours every detail.

The final movement of Norma Jeane’s life is her realist period—the years of Arthur Miller, her transition to the stage, and the deepening of her artistic ambitions. Miller, the playwright, the intellectual, sees in Monroe something others refuse to: a mind as well as a body, a woman who longs to be taken seriously. Some Like It Hot (1959) belongs to this period, a film that showcases her impeccable comedic timing but is also burdened by the strains of her unraveling personal life. Her marriage to Miller, which began as a refuge from the shallowness of Hollywood, becomes yet another disappointment. The cultural perception of their love story shifts—at first, she is his muse, his inspiration, the tragic figure the great dramatist will redeem. But as their marriage falters, the narrative turns. He becomes distant, frustrated with her instability, and eventually, she is alone once again.

Throughout Oates’ Blonde, the scandal is pervasive—on-screen, off-screen, implied, directly depicted. The novel suggests, often without explicit evidence, that Monroe’s time on film sets was rife with affairs, coercion, and unspoken power dynamics.

Oates, careful with legacy and legality, avoids direct naming where it would risk too much. The absence of explicit names does not dilute the sense of violation, however, of the suffocating machinery that shaped and consumed her. In a way, the blurred edges of these accusations make them all the more unsettling.

Monroe’s story, in Oates’ hands, thus becomes not just hers alone but the story of every woman used, remade, and ultimately discarded by the industry that promised to immortalize them.

In a revealing exchange with Emily Dinsdale for AnOther Magazine, Oates explained her unconventional approach to researching Blonde—one sparked not by an avalanche of biographies, but by a single evocative photograph that led her straight to Marilyn’s early films:

ED: “Reading Blonde, it seems like you did a vast amount of research. How did you locate your version of Norma Jeane from all of that material about her life that’s out there?”

JCO: "Well, I actually didn’t read that many biographies because I started with this photograph, and then I read a biography that just happened to be at the library that day. But then what I did was I went to her films and I saw all her movies, starting when she was just a starlet. She had very small roles in movies that are forgotten now but Niagara was the big breakthrough that made her a star; a sex object. She plays a voluptuous, beautiful woman and then, after that, she never played a role like it again. She sort of got shunted into this dizzy Gentlemen Prefer Blondes character, so she never really had a chance to develop as a strong screen actress."

When asked about her pursuit of what she called the “poetic truth” of Monroe’s life, Oates continued:

ED: I once heard you describe trying to access the ‘poetic truth’ of Marilyn Monroe’s life as opposed to documentary truth. Could you elaborate on that idea?”

JCO: I didn’t find it difficult to imagine Norma Jeane Baker’s interior life. I think most orphans and people who've lived in a succession of foster homes just become marginalized people, and they’re outside of a family looking in. They don’t have the feeling of being wanted or accepted that most of us have from having a loving family. I really could relate to that . . . She did keep a journal, she wrote little things in a notebook. So she had a side of her that was actually literary and poetic and thoughtful, but it was something that wasn’t really productive to develop because people were not interested in that side of her at all. But people who knew her said she was always reading a book, she was reading novels, she was a thoughtful, intelligent person who had to spend most of her time in a very extroverted way—caring about her costume, her hair, and that sort of thing.

Joyce Carol Oates’ remarks here reveal a deliberate, almost defiant approach to biographical fiction. She does not claim historical accuracy, nor does she dwell on exhaustive research. Instead, she speaks of poetic truth—a phrase that both elevates and absolves, signaling that her Monroe is not a reconstruction, but an artistic creation. She sidesteps the weight of documentation, beginning with a single photograph and immersing herself in Monroe’s films rather than the tangled accounts of her life. This is not the work of a historian but of a novelist determined to inhabit, rather than merely chronicle, her subject.

This raises the central ethical question of Blonde: Does the pursuit of emotional truth justify the reshaping of a real person’s legacy? Oates offers no apology for the novel’s liberties, nor does she acknowledge the potential harm in fictionalizing Monroe’s trauma. Instead, she insists on an intrinsic understanding, aligning Monroe’s orphanhood and lifelong search for belonging with broader themes of isolation and reinvention. Monroe, in this telling, is not just a woman, but an archetype—exploited, discarded, and immortalized in the same breath.

There is, however, a paradox at work. In seeking to humanize Monroe, Blonde subjects her to further voyeurism, reenacting the very forces that consumed her. Oates does not soften the brutality, nor does she offer redemption. The novel does not console—it confronts, forcing readers to sit with the discomfort of a life lived under a relentless, unforgiving gaze. Whether this is an act of empathy or another form of exploitation is a question Blonde refuses to answer, leaving Monroe, once again, trapped between myth and reality.

Blonde, Ulysses, and the Polyphonic Mind

James Joyce’s Ulysses (1922) did more than revolutionize the modern novel—it shattered it into pieces and reassembled it into something unrecognizably new, an artifact of literary modernism that defies conventional storytelling at every turn. Structured as an eighteen-part mirror of The Odyssey (800-700 B.C.E.), each episode adopts a radically different style, transforming the novel into a self-contained history of literary form.

Nowhere is this stylistic radicalism more “mindbending” than in “The Oxen of the Sun,” tracing the evolution of English prose within a single episode. Beginning in the grand, Latinate manner of early English writing, it moves through an accelerating series of pastiches—from Chaucer, to Shakespeare, Dryden, Defoe, Sterne, and Dickens, all the way back, all the way forward—before dissolving into a frantic, near-nonsensical explosion of slang, mimicking both the gestation of language and the development of a fetus. Like the fetus, the prose itself becomes a living, breathing organism, mutating as history unfolds.

Much like Joyce’s opus, Blonde employs a multitude of narrative tools to mirror the fragmentation of reality experienced by its protagonist. Oates harnesses a similar multiplicity, channeling the hyper-accelerated pace of post-war Hollywood and the disruptive influence of newly invented pharmaceutical drugs. This narrative fragmentation drives right to the heart the serious possibility of Norma’s addiction to painkillers and Benzedrine. Just as addiction fractures one's perception of reality—blurring past and present, self and spectacle—Oates’ shifting prose structure mirrors this instability. The novel does not simply describe addiction; it replicates its effect, forcing the reader to inhabit the same fragmented consciousness that Monroe endured. For anyone who has ever struggled with addiction, Oates’s depiction of Monroe’s own battle resonates as a raw and honest portrayal of how external forces can overwhelm the self. In Blonde, as in Ulysses, each stylistic shift invites the reader to perceive reality from a new angle—a prism through which the myth of a person is refracted into an array of vivid, sometimes conflicting, truths.

But if Joyce is Blonde’s literary ancestor in form, Dostoevsky is its spiritual forebear in scope and psychological depth. Oates, much like Dostoevsky, structures her novel around the collision of competing voices and perceptions, constructing a polyphonic narrative where no single truth dominates. Just as The Brothers Karamazov (1880) stages its philosophical debates within the minds and dialogues of its characters, Blonde unfolds as a series of internal and external interrogations, revealing the ceaseless questioning that defines Norma Jeane’s reality. Her inner life is a Karamazovian struggle, a constant wrestling between faith and doubt, self-belief and self-destruction, her own desires and the oppressive forces shaping her. Monroe's consciousness is not presented as a stable, linear entity but as a battleground of perspectives, where every voice—her own and those imposed upon her—clamors for primacy.

Oates achieves this Dostoevskian effect by shifting focalization among a myriad of figures who perceive Marilyn in different ways: the orphaned Norma Jeane, the Hollywood directors, the lovers who misunderstand her, the industry figures who mold and discard her, and the anonymous voices of public perception. Each of these perspectives forms a layer of her identity, much like Dostoevsky’s characters are shaped through debate, contradiction, and the ever-present pressure of ideological conflict. In Blonde, Norma Jeane’s mind itself is a forum where these competing forces engage, turning her self-conception into an ongoing dialogue of struggle, self-doubt, and existential reckoning.

Oates, like Dostoevsky, refuses to present her protagonist as a coherent, singular figure; instead, Monroe emerges as a shifting, debated entity—a consciousness shaped and fractured by the multitude of voices that seek to define her. Oates constructs Blonde around a fundamental split—the rupture between Norma Jeane, the fragile, searching girl, and Marilyn Monroe, the icon sculpted by Hollywood and public perception. But this division is not clean; rather than two distinct selves, it fractures infinitely, multiplying into a kaleidoscope of roles, identities, and performances that destabilize any stable sense of self.

These invented scenes. Improvised after the fact. They would plague her through the remainder of her life. Nine years five months of that life. And the minutes rapidly ticking. Could there be an hourglass of time in which time runs in the opposite direction? Had Einstein discovered that time might run backward, if a ray of light could be reversed? “But why not? You have to wonder.” Einstein dreamt with his eyes open. “Thought experiments.” That was no different really from an actor improvising as Norma Jeane did, after the fact. Which was why “Marilyn Monroe” would be increasingly late for appointments.

Not that Norma Jeane Baker was paralyzed with shyness, indecision, self-doubt staring at her luminous beautiful-doll face in whatever mirror of desperation and hope; no, it was the invented improvised scenes that held her. See, if there’d been a director and he’d said, OK, let’s run through this again, you would, wouldn’t you? Again and again—however many times required to get it perfect. When there is no director you must be your own director. No script to guide you?—you must compose your own script. In that way, so simple and clear a way, seeming to know what is the true meaning of a scene that eluded you in the living of it. The true meaning of a life that eluded you in the dense thicket of living it. In all this external search . . . an actor must never lose his own identity.

Oates plays with time as both a psychological and metaphysical concept—suggesting, through Einstein’s theories, that Monroe is caught in a paradox where the past is never truly past. The phrase “invented scenes” underscores the artificiality of memory, framing Monroe’s reflections as re-edited versions of events, endlessly replayed but never resolved. The fragmented, staccato rhythm of the opening lines—"These invented scenes. Improvised after the fact.”—mirrors the fragmented nature of Monroe’s consciousness, as if her life is composed of incomplete takes, each one demanding a retake that will never come.

This perpetual self-direction, this compulsive need to “run through it again” in search of meaning, renders her helpless against the passage of time. Monroe does not suffer from shyness or mere self-doubt, as others assume; she is held captive by the recursive logic of performance, where each moment of her life is both lived and staged, experienced and revised. If life is a series of takes, then she is forever chasing a perfection that will never arrive.

Blonde and the Violence of Mythmaking:

It is impossible to approach Blonde without reckoning with the sheer scale of its ambition, its ethical provocations, and its relentless descent into myth. Joyce Carol Oates does not simply recount Marilyn Monroe’s life; she excavates it, exposing raw nerves and placing her within a lineage of suffering that feels at once deeply personal and disturbingly preordained. The novel does not function as history, nor does it pretend to. Instead, it inhabits the space between what is known and what can only be imagined, wrestling with the contradictions of a woman whose reality was never fully her own to claim.

There exists an entire FBI list of Monroe’s supposed lovers—a document cataloging the men who orbited her like satellites: presidents, playwrights, athletes, and directors. Each name is a claim to intimacy, another piece taken from her, another fragment of the person she was never allowed to keep. But what does it mean to be desired when the self is already a kind of fiction? Again and again, Blonde asks this question, not as an elegy but as an existential horror, stripping away the artifice of Hollywood until all that remains is the woman—alone, yearning, punished for what she represents.

As for warning: the novel’s depiction of sexual violence is comparable to very little else in literature. Few books have so precisely captured the machinery of exploitation, nor rendered the body as a battleground where the lines between pleasure, coercion, and obliteration dissolve completely.

That Blonde (2000) was adapted into a film by Andrew Dominik—a director whose aesthetic obsessions run parallel to Oates’ own brutal vision—made its eventual NC-17 rating inevitable. Anyone who had truly read the novel could have predicted that Netflix was unleashing a nightmare, whether it understood it or not. Its reception, filled with outrage and unease, was not a failure but proof of its effectiveness. Monroe’s story, in this telling, was never meant to be digestible. It was meant to haunt. It was meant to wound.

By the time we arrive at Some Like It Hot (1959), the novel has escalated into full horror. Monroe’s final years unfold like a fever dream of betrayal and psychic collapse, the weight of her existence pressing down until it is unbearable. Even before the end, some moments threaten to alienate even the most steadfast reader—the rendering of Marlon Brando, for instance, a scene so deeply unsettling that it lingers long after the book is closed. Many have had their feelings hurt by this novel, by its depiction of the men who shaped Monroe’s life, by its refusal to soften the world she inhabited. But should Blonde be safe? Should it console rather than confront?

Oates’ approach is, in many ways, the extreme of biographical fiction, an aesthetic reminiscent of the Marquis de Sade—an unflinching commitment to exposing the brutalities of power, sex, and submission, indifferent to the audience’s comfort. Monroe is neither fully a victim nor entirely an agent of her fate; she is trapped in a system that feeds on her, adored for an image she cannot control, discarded the moment she falters. There is no romanticism here—no soft-focus eulogy, no gentle fade-out. Only the inexorable march toward the inevitable, the disintegration of a woman who, even in death, remains public property.

And yet, Blonde is not just darkness. Its power lies in its ability to hold horror and beauty in the same breath, to render annihilation and transcendence inseparable. Even in its bleakest moments, there is awe—at Monroe’s sheer presence, her luminosity, the way she exists beyond the sum of her tragedies. She was more than her image, more than her legend. So, too, is this novel—imperfect, yes, but imperfect in the way that Ulysses (1922) and The Brothers Karamazov (1880) are: sprawling, excessive, contradictory, and uncontainable.

To read Blonde is to be engulfed in something excessive—too much, too raw, too uncontainable. It isn’t history, but it feels more honest than history often allows itself to be. Like Monroe herself, the novel refuses to be pinned down, slipping between fact and fiction, intimacy and spectacle, until what remains is an absence that lingers—a presence defined by its disappearance.

What a fantastic review, Brock! I can only imagine the extensive reading, research, and analysis you undertook to represent the topic so well. I love how it resonates with the deep emotional nuances of Marilyn's life and captures the complex themes of Joyce Carol Oates's book. Well done! 👍

Oats could have easily created a fictionalized starlet, she kind of used Marilyn to sell books. My favourite Marilyn movie is The Misfits and I think if more people saw that film, they’d understand what a deep and really good actress she was.

(necrophiliac entertainment) I liked this line.

Good review you have some deep insights.

The only grave I’ve ever visited still to this day was Marilyn’s. We stumbled upon it wandering through Westwood, drinking a bottle of vodka like bad teenagers.. 😎

Great read.